The proposed entertainment complex planned for the property beside B.C. Place Stadium in Vancouver would include a 110,000-squarefeet, 24-hour casino, two international hotels and five restaurants. The proposed project would cost $450 million and developers hope to begin construction in early 2011. — PNG file

The proposed entertainment complex planned for the property beside B.C. Place Stadium in Vancouver would include a 110,000-squarefeet, 24-hour casino, two international hotels and five restaurants. The proposed project would cost $450 million and developers hope to begin construction in early 2011. — PNG file

complex more than 15 years ago, the city has changed its mind from red to blackJOHN BERMINGHAM

Province

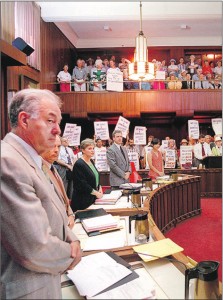

The-city councillor Don Bellamy (left) is seen with anti-casino groups in this 1994 file photo when they stormed the council chambers in Vancouver's City Hall. PETER BATTISTONI --PNG FILE

They’re rolling the dice again on a Las Vegas-style casino for Vancouver.

More than 15 years after Vancouver’s city council, the B.C. government and the majority of Vancouverites gave are sounding city’s waterfront, a similar casino-hotel complex is back on the table.

This time, it has the blessing of Premier Gordon Campbell, an ardent opponent of the 1994 proposal.

The new B.C. Place casino would turn a 700,000-square-foot parking lot into a luxury casino, complete with two hotels and five restaurants.

Back in 1994, Las Vegas gambling king Steve Wynn rolled into town with a proposal for a seafront casino.

It included a 1,000-room hotel, a cruiseship terminal and a permanent stage for Cirque du Soleil — along with the casino.

But city councillors voted it down unanimously after wide consultation and a heated opposition campaign by antigambling activists. The NDP government of then-premier Mike Harcourt also stepped in to ban destination-style casinos.

There were packed meetings, public rallies and a city poll that showed 52.3 per cent of citizens opposed the Seaport Casino, with just 30.2 per cent in support. A full 63.8 per cent were against any major casinos in Vancouver, with only 22.1 per cent in favour.

Times have changed. Campbell is now a champion of the B.C. Place casino, which will include a $563-million upgrade for the Crown-owned stadium, including a new retractable roof.

Given public comments, city council seems fine with moving the Edgewater Casino into the new casino from its current home at the Plaza of Nations on False Creek. And public opposition, so far, has been muted, limited mostly to the concerns of the nearby condo residents.

So how did the city go from red to black? How have things changed since 1994 that now makes the mega-casino a short-odds bet? Here’s a look at some of the ways Vancouver has changed in the 15 years since the last big casino was proposed for downtown:

City image

Then: In 1994, Vancouver’s image was seen as an economic asset. The NPA-led city council felt the city’s image involved its setting, safety, cleanliness and relaxed lifestyle. The city manager’s report to council said most people were concerned about how a huge casino would affect the city’s image, arguing that “major casinos are not in harmony with the Vancouver they value.”

Now: University of B.C. community planning professor Michael Seelig, a vocal anti-casino opponent in 1994, says Vancouver should build on its success during the Olympics, when the city’s beauty was on display, and not go the Las Vegas route.

“Do you really want to become known as a gambling city?” Seelig asks. “ Vancouver does not need to have a facility that size that doesn’t really add much to the local population.”

Housing

Then: A discussion paper on the 1994 casino proposal said any inner-city casino would impact affordable housing, especially single-room-occupancy hotels. The area around the casino might be gentrified, and the social-housing stock reduced. A successful hotel would boost real-estate values in the area, with the effect of raising property taxes, it argued.

Now: With thousands of apartments surrounding B.C. Place, taking in Yaletown, Northeast False Creek and the Downtown Eastside, a mega-casino could still impact real-estate values.

“It’s a trade-off,” says Tsur Somerville, a real-estate economist at UBC’s Sauder School of Business. “On the one hand, a casino creates more commercial activity, there are more people, and that increases commercial values.

“On the other hand, the casino environment itself isn’t necessarily the kind of street life that all buyers want.”

The inner-city’s rental-housing stock has been increasing, under the B.C. government’s partnership with the City of Vancouver. But a luxury casino could add more pressure to gentrify low-income housing.

But Somerville says the pressure to re-develop the Downtown Eastside is already so strong that a new casino would have a marginal impact.

Then: The city’s casino review said a major gaming facility would most affect the neighbourhoods in the immediate area. It predicted traffic and parking concerns, noise and a threat to park space.

The impact on local businesses could also be a major issue, it said. And there would be a challenge fitting a casino the size of five football fields into the city’s waterfront skyline.

Now: Former Vancouver mayor Philip Owen, who voted against the 1994 proposal, lives just two blocks from the proposed new casino. He says Yaletown will be deeply impacted by a 100,000-square-foot casino, with 40 restaurants currently in the area.

“I think it’s going to be maybe a hard sell,” says Owen. “You better go through the process. You consult with the neighbourhood.”

Some Yale town and False Creek residents have already expressed their concerns.

Local business

Then: The debate among the city officials in 1994 focused in part on how many tourists would come to gamble in Vancouver. The more of them, the merrier, they concluded.

But if more locals gambled at the casino, it would divert dollars away from other parts of the local economy.

Now: Charles Gauthier, speaking for the Downtown Vancouver Business Improvement Association, says the new proposal doesn’t compare to 1994.

Back then, he says, the proposal was far more grandiose and was located away from local businesses. The new casino would be much more integrated into an already-established commercial district, he says.

“I don’t think that is going to detract from the amenities,” says Gauthier.

Deanna Geisheimer, who owns the Art Works Gallery in Yaletown, figures it will a destination venue for people who go there to gamble.

“We all basically have our client base, who already come to us,” she says. “It will probably give us as much as it will take away.”

Crime

Then: The casino review expected that more police would be needed to deal with problems like money laundering, loan sharking, fraud and prostitution.

There was also a concern a large casino would be a magnet for organized crime, attracting criminals to Vancouver.

At the time, there were fears of a rise in overall crime due to gambling, but a look at the experience of the casino in Windsor, Ont., found that police were able to contain it successfully.

Now: Vancouver police spokes woman Const. Jana McGuinness says police have had very few complaints about the current Edgewater Casino on the old Expo site.

“There really have been no incidents of note,” says McGuinness.

Police have responded to the odd call about alcohol at nearby nightclubs, or cruises, she says, and recently, a woman was charged with leaving her child in a car while she gambled at the casino.

Simon Fraser University criminologist Rob Gordon says public gaming reduces illegal gambling, and stops the drain of gambling dollars to the U.S.

“In many respects, the argument that casinos act as a magnet for predatory street crime is a bogus argument,” says Gordon. “Casinos are not more criminogenic than any other places that cater to large crowds.”

© Copyright (c) The Vancouver Sun