180,000 bees at the Fairmont Waterfront sweeten the menu at hotel’s restaurant

Mia Stainsby

Sun

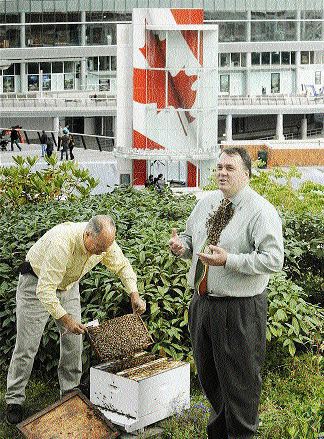

John Gibeau (left), president of Honeybee Centre, and Graeme Evans, Fairmont Waterfront’s director of housekeeping and resident beekeeper harvest honey from hives on the hotel’s terrace as Evans starts working on a bee beard. Photograph by: Glenn Baglo, Vancouver Sun

Graeme Evans shows off his bee beard. Photograph by: Glenn Baglo, Vancouver Sun

Assistant restaurant manager Kate Lattik serves up honey fresh from the hive to visitors from Andre Piolat school in North Vancouver. Photograph by: Glenn Baglo, Vancouver Sun

Photograph by: Glenn Baglo, Vancouver Sun

Chatting with Allen Garr, a journalist who also happens to be an urban beekeeping advocate, I’m happy to learn that honeybees, unlike wasps, are not carnivores. They don’t sting you, like wasps, unless you go asking for it. “I’m not sure if they’re vegans,” he adds.

So I cannot say it took any courage at all to meet some 180,000 honeybees at a third-floor rooftop apiary at the Fairmont Waterfront in Vancouver, just across the street from my office. In fact, it’s one of five Fairmont hotels in North America with bees buzzing around the property. And, after talking bees with the hotel’s beekeeper, I see a morality tale in the life of bees, which I’ll get to later.

At the Waterfront, bees check into three white condos, known as supers in the apiculture world. I can see a few bees lighting on flowering plants in the organic bee garden nearby. Looking down the street, I see the Vancouver Convention Centre’s grass roof. Soon there will be beehives there, too.

As to why we’re seeing more and more honeybee hives in public facilities, it’s becoming very clear. Without them, we’d have a radically different diet and I’m not talking about the lack of honey for our tea. About a third of cultivated crops depend on pollinators, and in Canada, honeybees are the most common pollinators.

“Without bees, 90 per cent of our food crops would diminish. Every flowering tree would die. We’d be left with corn, beans, wheat, rice, that’s it,” says Graeme Evans, the hotel’s director of housekeeping who became the resident beekeeper, thanks to his passion for bees. “In fact, we wouldn’t have the feed for cattle, chicken and pigs. Some say in the worse case scenario, if current rates of decline continue, we’d be out of bees by 2024. That’s why we do what we do.” Ditto the Paris Opera House, the White House and Chicago City Hall, apparently.

Garr, the beekeeper at the VanDusen Botanical Garden, UBC Farm, Science World and the UBC Botanical Gardens, says some 30 to 35 per cent of colonies were lost in the last year. “It was the same the year before and the year before that.” Disease, pesticides, herbicides, monoculture agriculture and habitat loss account for a good part of bee loss.

“I stand at Science World and I can see why they’re not thriving,” he says. “I look out and see steel and glass. There used to be banks and banks of blackberries growing there, an excellent source of nectar and pollen for bees; so by continuing to denature the city, removing pollen and nectar sources, we’re destroying bee habitat.”

The Fairmont Waterfront started with 60,000 bees last year and currently has around 180,000. The bees have a feeding radius of six kilometres and that includes the hotel’s own herb garden and Stanley Park. This year, they’re expecting to harvest 400 pounds of honey, which will be used by the hotel’s kitchen, and also bottled for guests. As the hotel colony grows, excess bees are split off and taken to the Honeybee Centre in Surrey where they continue to form additional colonies.

Recently, Evans captured a rogue hive of 10,000 bees from Stanley Park, which had gathered on a tree next to Fairmont Waterfront. Normally, Evans is like Jeeves, beekeeping in his impeccable suit and tie — sometimes he’ll use smoke to calm the bees — but on that occasion, he was more like Neil Armstrong in a space suit. He’s been stung five times altogether, but he’s developed a tolerance to stings. Besides, he says, for the sake of guests, the hives contain Italian honeybees, “known for their gentle demeanour.”

Evans can follow summer in the honey. “Right now, they’re bringing in a citrusy caramel flavour. It’s absolutely sublime. It’s from a lot of sources. If you go further down in the hive [bees deposit their honey in a semi-circular pattern], we’ll get licorice flavour coming from the fennel in our garden. It’s such a strong flavour that even a small amount of nectar flavours the entire honey. Our chef uses this for duck and rolling pecorino cheese. It’s excellent with wild salmon. Even further down the comb, there’s minty flavour. You can see the different colours from when they’ve extracted from different sources. The first flow is when our lavender comes out, but blackberry and raspberry are mixed in there, too,” he says.

The hotel’s chef, Patrick Dore, incorporates honey into the lunch, dinner and cocktail menus at Herons Restaurant and Lounge and through September, the restaurant will feature a $49 honey menu which includes a honey lavender vinaigrette on a salad, honey-roasted duck breast, apple pie with honey goat cheese ice cream and a mignardise of honey and white chocolate truffles.

“It’s like a tie-in with the 100 Mile Diet, which has gone viral,” says marketing director Kevin Schmidt. “This is more like the 100-foot diet.”

Highlighting the work of bees, Evans says an apple tree in the hotel garden previously yielded about 20 apples a year. Since bees were brought in, it produces more like 200. “The bees’ interaction with its flowers excites the trees,” he says, ensuring he doesn’t anthropomorphize the bees.

And yet, we end up talking about bees as if they were people. He loves their moral sense. “Their entire culture is derived around keeping the hive alive. Every bee produces one teaspoon of honey. Together, they can produce 360 pounds. We sometimes struggle in our own society with feelings of powerlessness and what we can do in the face of global warming. What if every bee thought that way and gave up on the one teaspoon?” he says, Socratically.

“If everyone does one thing to improve sustainability, think of the massive impact. It’s a very good lesson in cooperative management.”

© Copyright (c) The Vancouver Sun