EXPO 86 I The city opened its door and became more livable, more sophisticated and a lot more interesting

Doug Ward

Sun

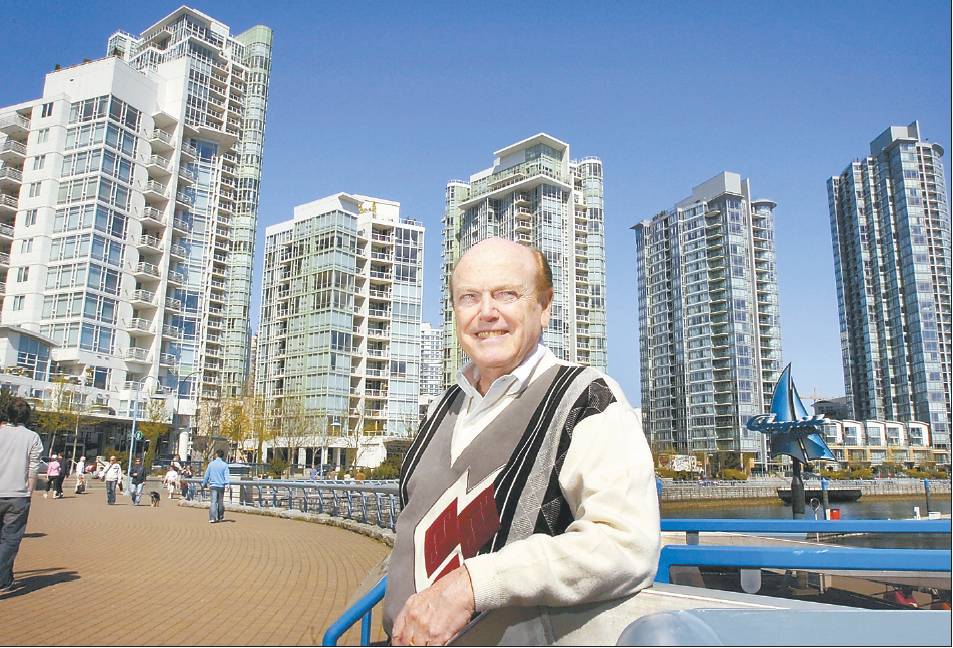

IAN LINDSAY/VANCOUVER Jimmy Pattison, who became Expo 86 president, returns to the False Creek site of the fair, which he says succeeded beyond everyone’s expectations.

VANCOUVER SUN FILES Expo 86 was marketed as a fun event with parades, fireworks, distractions and late-night partying.

Diana, Princess of Wales, chats with Vancouver-based rock star Bryan Adams at the Expo Theatre in Vancouver in 1986. Adams was one of many performers who took part in a gala rock concert at the fair. Photograph by : Ryan Remiorz, Canadian Press Files

Expo 86 crowds in October 1986. The final count of 22 million visits far exceeded the fair’s original projection of 13.7 million. Photograph by : Bill Keay, Vancouver Sun files

Back in 1948, long before he began making his billion-dollar fortune, Jimmy Pattison worked in the windowless pantries of CP Rail passenger trains.

He made salads, often cut his hands cracking ice and slept on tables. Upon his arrival back in Vancouver after trips to Calgary, Pattison and other crew members would be unloaded at the CPR rail yards on the north shore of False Creek.

Pattison recalled that summer job recently as he returned to the CPR’s former western terminus site. The place he visited is now better known as the site of Expo 86 — the world’s fair that opened 20 years ago on May 2 and is now seen as the pivotal event marking Vancouver’s late-20th-century coming of age.

Pattison stood along the False Creek waterfront and recalled how the area was once home to railroad tracks, factories and lumber mills. These days, the land along the inlet is dominated by a forest of towers inhabited by white-collar middle-class professionals, many of whom shop at the nearby upscale Urban Fare, owned by Pattison himself.

On the afternoon of his visit to the scene of Expo, Pattison ran into Vancouver Mayor Sam Sullivan and venerable band leader Dal Richards. Both men live in nearby condos built as part of the post-Expo real-estate boom downtown.

“It’s really wonderful — what’s happened in downtown Vancouver,” said Pattison.

“Where we were and where we are now is a big difference, no question about that.”

As a point in time, Expo stands at the juncture of two Vancouvers — the old village on the edge of the rainforest and the new post-industrial landing strip for capital.

Pattison said the 165-day fair, which drew Diana, the Princess of Wales, Liberace, the Soviet Soyuz spacecraft and your aunt and uncle from small-town Saskatchewan, succeeded beyond everyone’s expectations.

“But it seems like the traffic never went back to what it used to be,” said Pattison, who was famously paid $1 to be chairman and later president of the Expo Corporation.

“Our slogan was invite the world. And they came. They showed up.”

Yes, and as some people have lamented, the world stayed.

Which was the hope of most of Expo’s political and business backers all along.

Kris Olds, a geography professor at the University of Wisconsin, has written about how Expo was the “perfect resolution” to the desire of B.C.’s political and business elites to forge links with successful Asian economies and become a centre for Pacific Rim commerce.

Expo’s motto was “World in Motion — World in Touch,” which in hindsight is apt considering how Vancouver used Expo to get in touch with — or grab onto — a fast-moving world.

Vancouver became busier and less affordable. Expo critics in a recent Discover Vancouver bulletin board on the Internet said: “All the funky little boutiques on Robson became chain stores. Traffic congestion increased. Rents went up, housing costs went up. My earning capacity did not. Expo 86, I hate you.”

But as a character in the highly popular Spirit Lodge, at the General Motors Pavilion, said: “To stop moving is to die.”

Traffic, chain stores and high-priced real estate notwithstanding, Vancouver became more livable, more sophisticated and a heck of a lot more interesting — post-Expo.

A new middle class came to live in Vancouver’s downtown close to the city’s booming service and information economy. Vancouver became the envy of city planners across North America.

Besides marketing Vancouver to the world, Expo was accompanied by significant government-funded infrastructure, including Canada Place, Science World, the Plaza of Nations, SkyTrain and the Cambie Bridge.

So Expo’s significance extended beyond the fair, which was organized according to the dictum set by its first president, the American Michael Bartlett: “You get ’em on the site, you feed ’em, you make ’em dizzy, and you scare the s— out of ’em.”

“I don’t want to downplay the fair at all,” said Vancouver planning director Larry Beasley, “but at other world’s fairs, amazing things happened, but not much else happened afterwards.

“In our case, Expo was just the beginning because it happened at such a pivotal moment when we were in search of a new image for our city.”

Expo Ernie — or at least the remote-controlled voice of Expo’s mascot — couldn’t agree more.

“Vancouver had a different feel to it afterwards. Vancouver wasn’t a secret anymore,” said GraigWheeler, who guided one of the six Expo Ernie robots on promotional tours and at the fair.

Wheeler, who talked to crowds through a microphone in Ernie’s chest, said what he loved about Expo wasn’t any particular exhibit or pavilion, but just the energy that came with “having a community the size of Kamloops or Kelowna all in one place. I was just happy sitting at a cafe or The Unicorn pub and watching people.”

But the best thing about Expo, said Wheeler, now a landscaper, was that it changed how we saw our city. “We weren’t that sleepy little city. We were now able to hold our heads up and expect that someone from another part of the world would know about Vancouver. It produced civic pride.”

Expo 86 ran between May 2 and Oct. 13, 1986. The final count of 22 million visits far exceeded the fair’s original projection of 13.7 million. Expo’s total cost of $1.5 billion was shared by Ottawa and Victoria and corporate participants. The $311-million deficit was covered by provincial lottery revenues.

There are more numbers: The average daily attendance was 120,000 and the single-day record was 341,806, 54 nations participated, there were 70 restaurants and 43,000 entertainment performances, over 25,000 full-time jobs were created for six months, $20 million was spent on amusement ride tickets and $94 million on food, including 4.2 million hot dogs.

Expo was truly an event of mega-consumption.

And a good investment, according to conventional wisdom these days.

“Expo gave Vancouver the attention of the world in ways that we didn’t have before,” said Bob Williams, the former NDP cabinet minister who like many on the political left was a critic of Expo when Socred premier Bill Bennett first proposed it in 1980.

Williams described himself as a “reverse snob” about Expo: initially he felt Expo was a frivolous event, a bread-and-circuses project designed to make the masses forget about the economic hard times under Bennett in the early ’80s.

“But Expo really did have a substantial impact,” continued Williams, saying it catapulted Vancouver’s presence in the global marketplace ahead by about two decades — and set the stage for the new downtown.

“In a sense it was a preliminary to the downtown Vancouver, which we now celebrate and enjoy.”

Inadvertently, Bennett set the stage for the dense livable city state, said Williams, which was later designed by Vancouver city planners inspired by left-wing urban theorist Jane Jacobs.

Bennett himself is proud of Expo 86 and its legacy — proud enough to make a rare public appearance on Tuesday, speaking to the Vancouver Board of Trade about the Expo experience.

In an interview recently, Bennett said Expo came together because of a variety of factors. He recalled how then-Socred tourism minister Grace McCarthy travelled in 1978 to London where she met with Patrick Reid, who was Canada’s high commissioner.

McCarthy was wondering how to celebrate Vancouver’s centenary. During their lunch, Reid told McCarthy that he was also president of the Bureau of International Expositions in Paris. McCarthy asked why Vancouver had never been chosen as a site for a world exposition and Reid said, “because it never asked.”

(Actually, McCarthy first suggested to Reid that perhaps Vancouver could borrow the Mona Lisa from the Louvre in Paris and make that the centrepiece of Vancouver’s celebration — but that’s another story.)

Over time, McCarthy’s desire for a world’s fair in Vancouver coincided, recalled Bennett, with his government’s plans to build a stadium in Vancouver and get a rapid transit system and a convention centre. The transportation fair, originally called Transpo 86, was seen as way to leverage federal funds for some of the projects.

In late 1979, two Bennett advisers — Paul Manning and Larry Bell — recommended that the world’s fair be linked to the stadium and built on the False Creek lands owned by the CPR.

In January 1980, Bennett, facing poor opinion polls and a declining economy, announced the development of British Columbia Place, which would tie all these goals together, with Expo being the exclamation point set for 1986.

“I think for us it took some courage,” said Bennett, looking back. “B.C. had been in a downturn with forestry not at its best, and sometimes, you need to put things together to create excitement so that people can feel more confident.

“And getting the fair, the stadium and SkyTrain and everything else did that.”

Everything came together, but not always easily. Expo’s first president, Bartlett, was fired by Pattison in 1985 for allegedly being a big spender and not having the sensitivity required to run a public corporation beholden to government. Pattison blew a gasket when he walked into the Expo parking lot and spotted the $50,000 Mercedes Benz bought by Bartlett with public funds.

Bartlett later rejected Pattison’s accusations of extravagance, saying that he paid the difference himself between the car and the lowest price of any of Expo’s leased cars.

Bartlett also said that it was him — not Pattison — who “took Expo from a small regional experience to a large international event that was an exceptional success.”

A dispute between B.C.’s building trades unions and the Socred government almost killed the entire fair. The Socred government wanted a no-strike guarantee and it also wanted the Expo site to be open to non-union firms. Pattison negotiated a series of deals for labour peace but Bennett scuttled them. At one point in 1984 the labour situation looked so bleak that Pattison recommended to Bennett that he cancel the fair — advice the premier declined.

A deal was eventually struck with the unions, but Expo still looked like a dicey proposition. In 1984, Vancouver Sun columnist Denny Boyd wrote: “Expo has to die and Premier Bill Bennett must do the killing.”

Another Sun columnist, Marjorie Nichols, compared the Socreds to the dictators of impoverished Ethiopia who staged a gala banquet replete with imported French wines. She called Expo a “big, glittering, attention-riveting, reality-deflecting untruth about the province of B.C.”

Expo generated bad press for B.C. because of the eviction of low-income residents from residential hotels and rooming houses being upgraded for the Expo tourist trade. Olaf Solheim, an 88-year-old Downtown Eastside resident facing eviction, committed suicide. Legendary folksinger Pete Seeger staged a free concert in his memory.

But by the time Prince Charles and Diana opened Expo, former critics of the fair were prepared to attend, including then-mayor Mike Harcourt and prominent New Democrats.

Socred-haters were tortured over whether to attend an event so identified with Bennett, but many set aside their consciences and walked through the turnstiles.

There were a few missteps: Diana fainted following a three-hour Expo tour. More tragically, a nine-year-old Nanaimo girl was crushed to death between a rotating theatre stand and a wall in the Canadian pavilion.

The foreign press loved Expo, including E.J. Kahn of The New Yorker, who gave the fair “somewhere between a B-plus and an A-minus,” and remarked: “It’s not so much Expo 86’s substance that accounts for its charm as it is its style. The scene has an ambience of gaiety, even whimsy. You feel good just walking around.”

Less enamoured of the middle-brow Expo was Saturday Night magazine’s Robert Fulford who wrote: “The fair was reasonably well-attended, but it was a success in no other way. The exhibits were seldom adventurous or surprising and were often mundane. The films were in most cases predictable. The architecture, with few exceptions, was commonplace or worse.”

But the customers, who are always right, kept walking through the Expo site, with few complaints, except about the lineups.

And the press, once so caustic about Expo, jumped on the bandwagon when the nightly fireworks began.

Sun columnist Vaughn Palmer noted just days after Expo’s closure that “this time all the negative nellies were wrong and the cock-eyed optimists were right.” He added: “So long beautiful. We’ll miss you.”

n

In hindsight, Bennett’s Expo is seen as a great idea well-executed. But it was the timing that made Expo so significant in the long term.

Expo occurred just before a major jump in immigration between Hong Kong and Vancouver, due to Hong Kong’s 1997 repatriation to China, and the 1989 Tiananmen Square crisis.

Mega-events such as world’s fairs are designed to attract potential property investors, both local and foreign.

Among the more than 22 million visits to the fair were many Asian investors looking for places to park their money.

And among these were relatives and business associates of Li Ka-shing, Hong Kong’s richest property tycoon, who would later buy the entire 80-hectare Expo site from the B.C. government for $320 million.

Li wanted to provide his son, Victor, with a high-profile project to develop his expertise and establish a more significant North American base for the Li empire, said the University of Wisconsin’s Olds.

The urban geographer believes that the purchase of the Expo lands was even more critical to Vancouver’s development than Expo 86 itself, though it was the exposition that set the stage for the dramatic purchase.

While that purchase has been criticized as a poor deal made by a privatization-obsessed premier Bill Vander Zalm, others say it was a striking gesture that attracted more off-shore investment to the region and set the stage for the massive real estate project built by Concord Pacific under design guidelines set by city hall planners.

“Expo was quite pivotal because it provided a way to bring this huge piece of property into development in a generation,” said planning director Beasley.

He said the sale of the entire site to one developer gave city hall the leverage to get better design and more amenities than if the land had been sold piecemeal over time.

Expo 86’s influence can be overstated, said Olds, because the flow of immigrants and capital from East Asia would have come eventually, given the uncertainty in that region and changes in Canada’s immigration polices, including the business immigration program.

“Expo was in many ways more of a marker or an accelerator rather than the cause of Vancouver’s transition from the old-style Vancouver to a city with a more global metropolitan and cosmopolitan identity.”

Lance Berelowitz, author of Dream City: Vancouver and the Global Imagination, moved to Vancouver from his native South Africa via London in the year of Expo.

He recalled sitting with his wife on the deck of their rented Mount Pleasant apartment in the summer of 1986 and watching Expo’s nightly fireworks. He visited Expo a few times, failed to find much “intellectual depth,” but “it was a fun fair with fireworks, distractions and late-night booze.”

He said Expo alerted the rest of the world to the fact that Vancouver was “a beautiful place with undervalued property relative to other cities and people began to snap up the waterfront property with front rows to the city’s views.”

Berelowitz said Expo “was like Vancouver coming out at a debutant ball: ‘Hi guys. We’re here, we’re sexy and we have this to sell. What do you want to buy?'”

© The Vancouver Sun 2006