Critics ask for changes to reduce costs to homebuyers

Gordon Hoekstra

The Vancouver Sun

The B.C. property transfer tax is one-per-cent on the first $200,000 of the purchase price and two per cent on the portion of the price above that. First-time homebuyers don?t pay the tax on homes under $475,000. The formula has not changed since 1987. Photograph by: Mark van Manen, Vancouver Sun

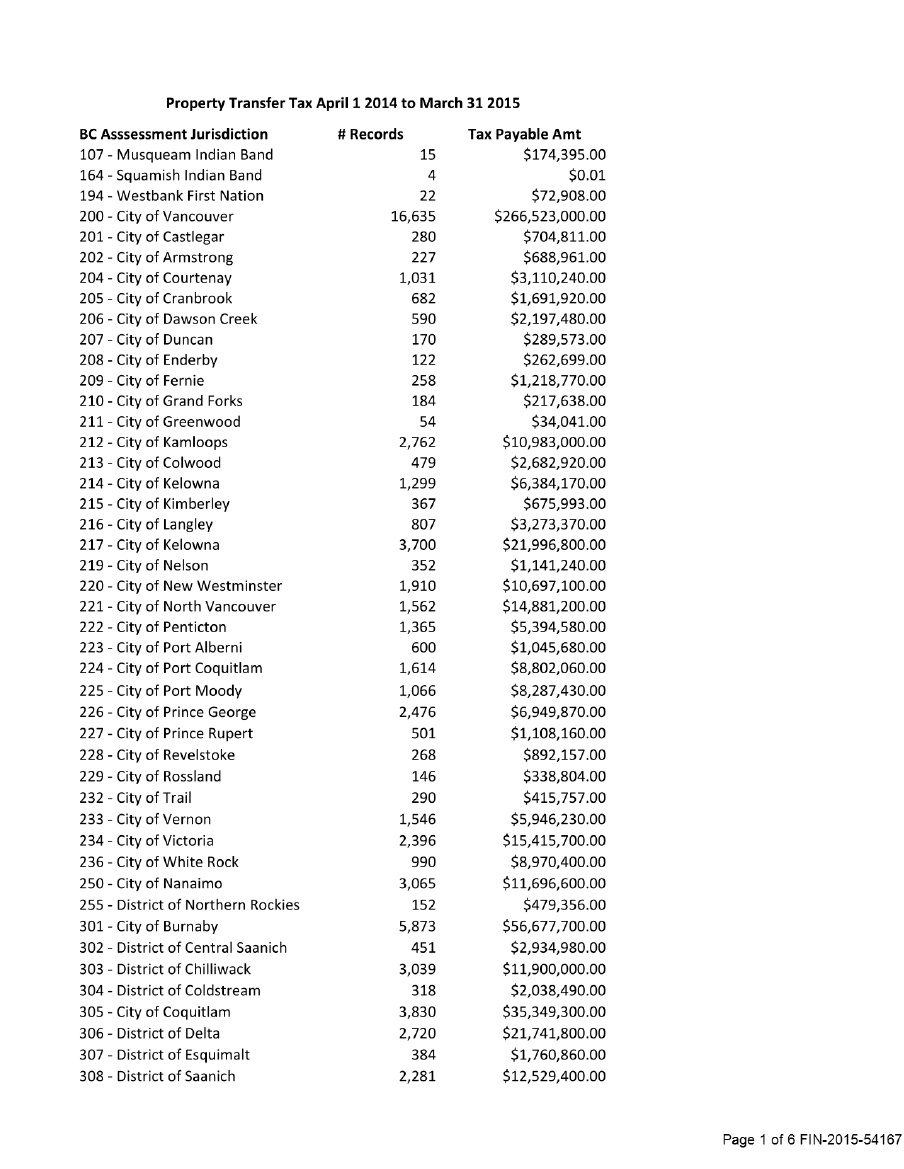

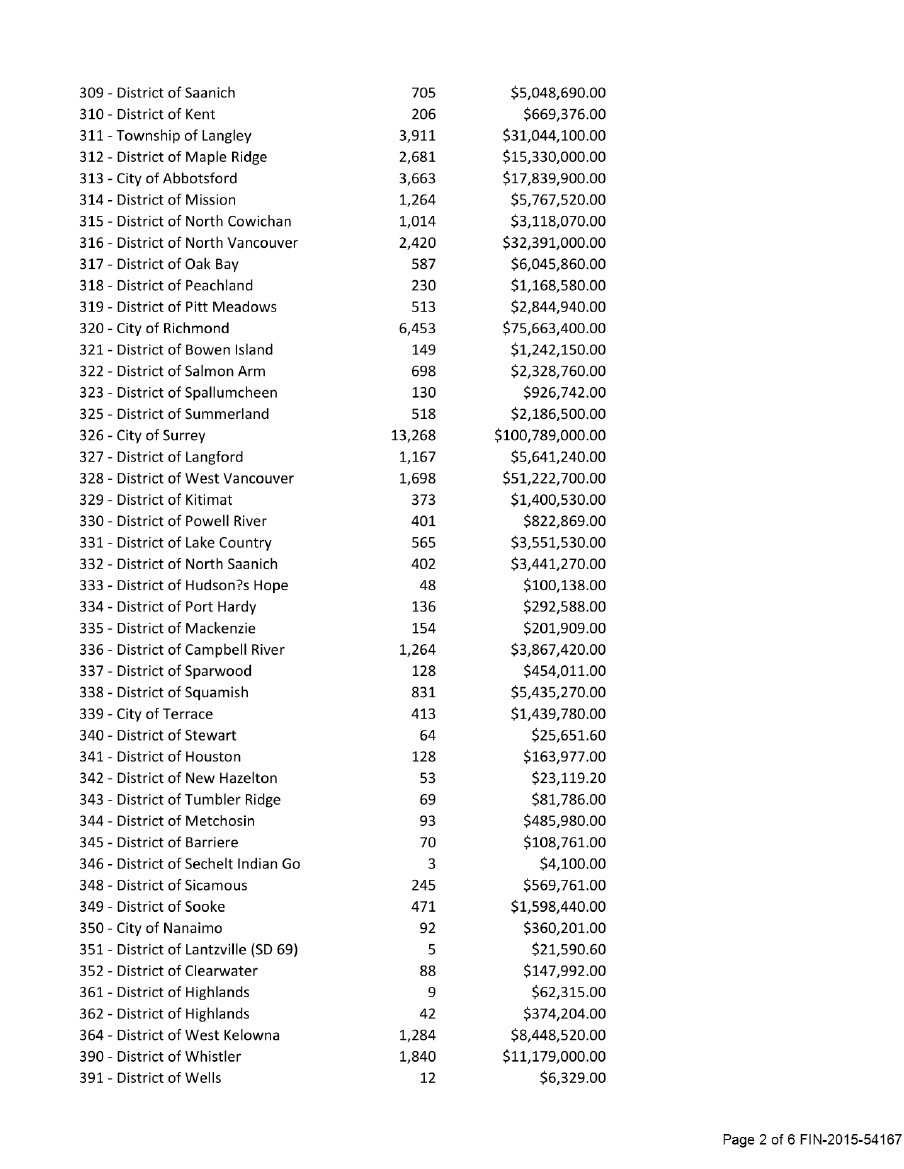

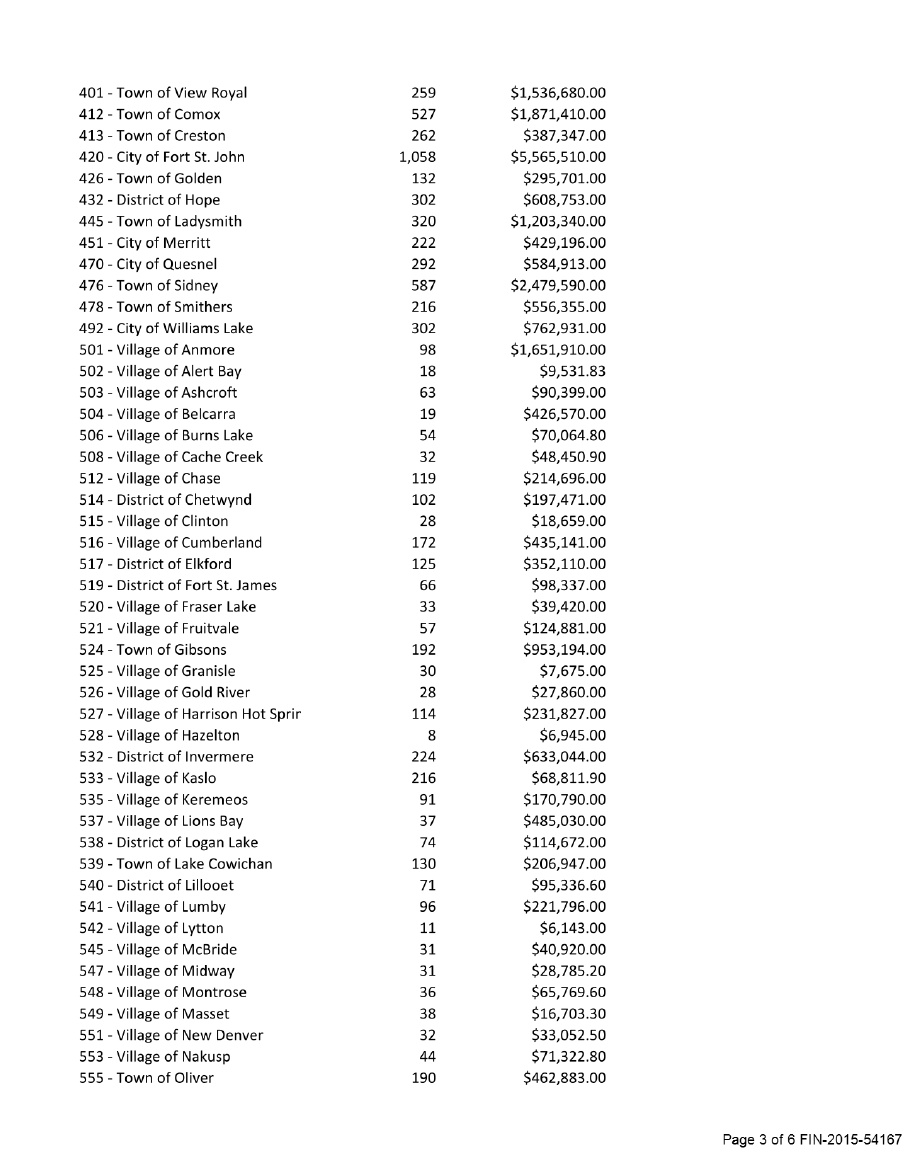

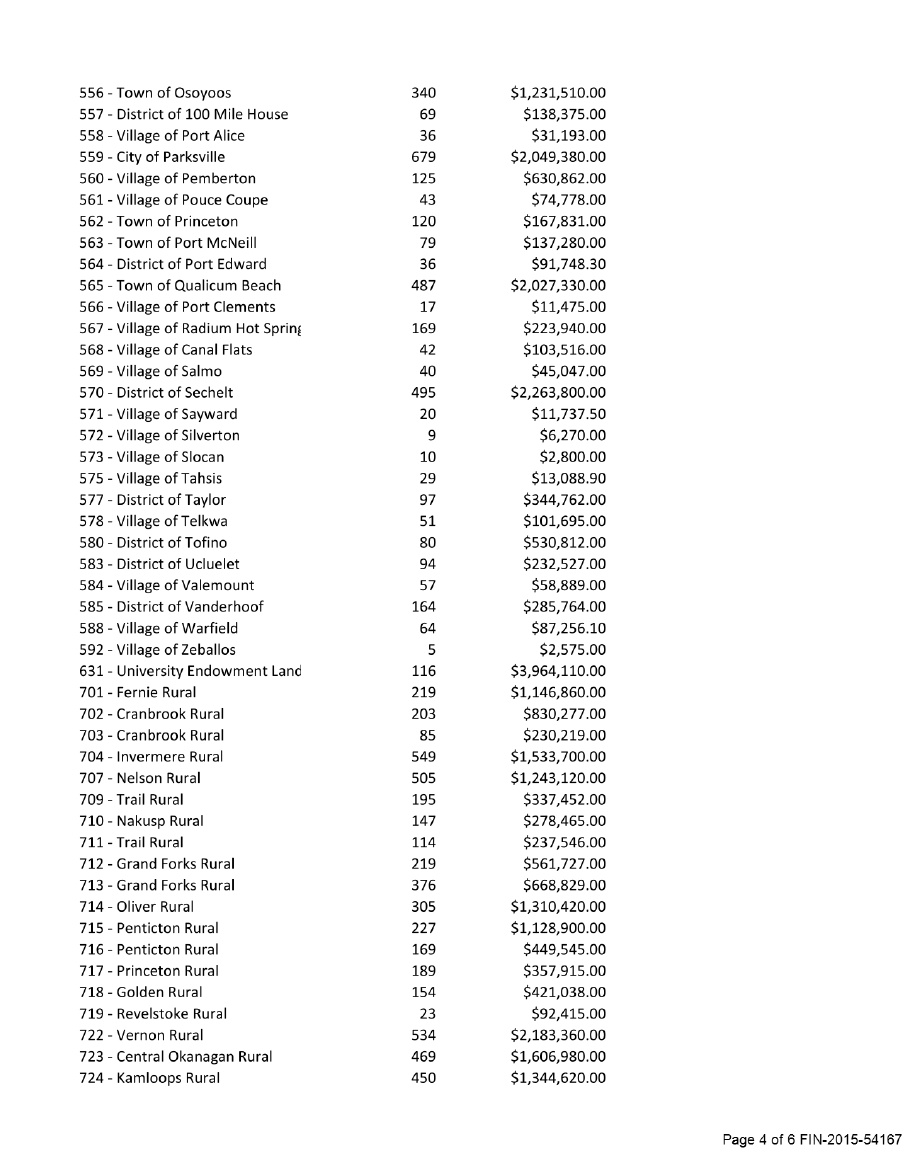

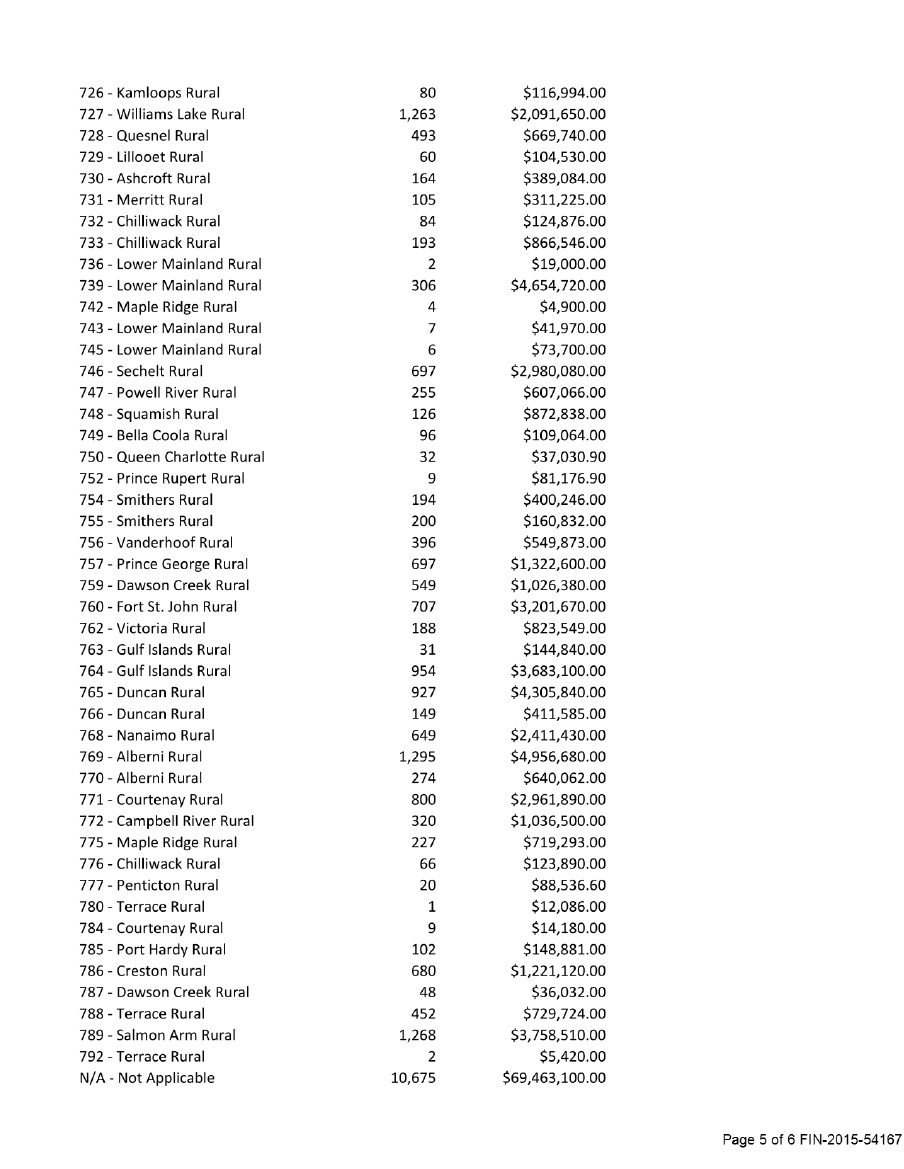

Vancouver accounted for nearly one-quarter of the government’s $1.15-billion windfall from B.C.’s property transfer tax in the past fiscal year.

The $266.5 million collected in the City of Vancouver in the property transfer taxes from 16,635 transactions in the 2014-2015 fiscal year ending in March 31 shows how Metro Vancouver’s overheated market is increasing this tax revenue for the B.C. government.

The remaining top-five sources of property transfer tax revenues were: Surrey ($100.8 million) Richmond ($75.7 million), Burnaby ($56.7 million) and West Vancouver ($51.2 million).

The top five municipalities accounted for $551 million in property tax transfers in 2014-15, more than half the total.

The information was revealed in a freedom of information request from an individual posted on the B.C. government’s open information website.

The take from 2014-2015 is up from $937 million in 2013-2014 and $889 million in 2012-2013, according B.C.’s public accounts.

The tax haul is expected to grow in the 2015-16 fiscal year that ends March 31.

University of B.C. economist Tsur Somerville said the municipal breakdown is not surprising in the least, as sales are reaching all time highs in the Lower Mainland and prices have been rising, up about 15 per cent year over year.

He said one worry about the rising property transfer revenues is that they are fundamentally cyclical revenues, and he believes they will go down at some point.

“I worry that you get a situation where the government becomes addicted to this revenue stream and therefore having the market not being heated is bad for government revenues,” said Somerville, director of the Centre for Urban Economics and Real Estate at the Sauder School of Business.

“I don’t think a government that’s constantly pumping up a housing market is where we want to be. I am not saying that’s what is happening, but you certainly create the incentives for that when so much money is tied to high prices and high levels of sales. That’s not super healthy,” he said.

The B.C. Liberal government has already acknowledged that returns from the property transfer tax this year are above forecast, and largely attributed to the hot residential market in Metro Vancouver.

B.C. Finance Minister Mike de Jong has also acknowledged that the property transfer tax windfall was helping keep the province’s budget out of the red.

There is some public expectation that the Liberals will make changes to the property transfer tax when they deliver the 2016-17 budget next week.

A one-per-cent tax is paid on the first $200,000 and two per cent on the portion of the purchase price above that.

First-time homebuyers don’t pay the tax on homes under $475,000.

De Jong has hinted at raising the two per cent threshold and also suggested the government may consider a third threshold at the high end of the market that could provide relief at the lower end.

NDP housing critic David Eby said a big concern for him is that while families buying homes have to pay the property transfer tax, commercial entities use bare trusts to avoid paying the tax and realtors using so-called shadow flipping are also not paying.

For families not buying a first home, the property transfer tax on a $600,000 property would cost them $10,000.

In shadow flipping, real estate brokers use an obscure assignment clause in sales contracts to allow the property to change hands — and the price to increase — multiple times before a deal closes. The technique drives up prices and commissions.

The final buyer pays the property transfer tax on the final purchase price. Because only one sale is registered, it lets the middlemen dodge the property transfer taxes.

“It’s clear to me that the rate would be lower for everybody and still generate the same amount of revenue if the government just closed these obvious loopholes in this tax,” said Eby.

B.C. Real Estate Association spokesman Damian Stathonikos said they have been asking for some time for the province to raise the threshold on the two-per cent tax to $525,000.

The property transfer tax was introduced in 1987 as a “luxury tax,” but Stathonikos noted the thresholds have not changed since then, meaning it has turned into a revenue generator for the province.

He said the province should index any changes so the tax will move as house prices increase over time.

© Copyright (c) The Vancouver Sun