many charms: Art galleries, festivals and colonial architecture lure visitors who end up becoming residents

Lisa Monforton

Province

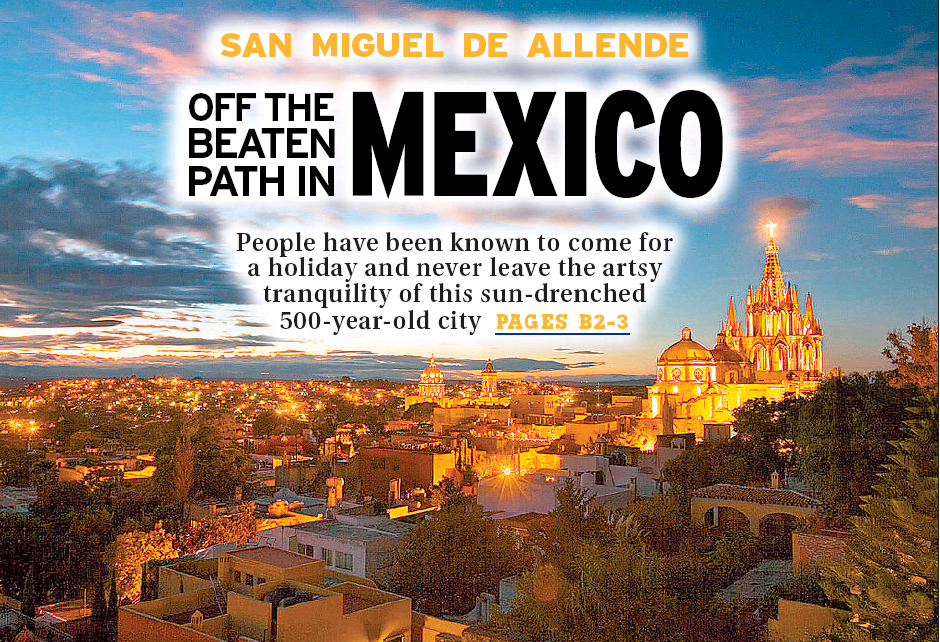

La Parroquia, the iconic parish church in San Miguel, glows with lights and the setting sun. — BALD MOUNTAIN DE MEXICO

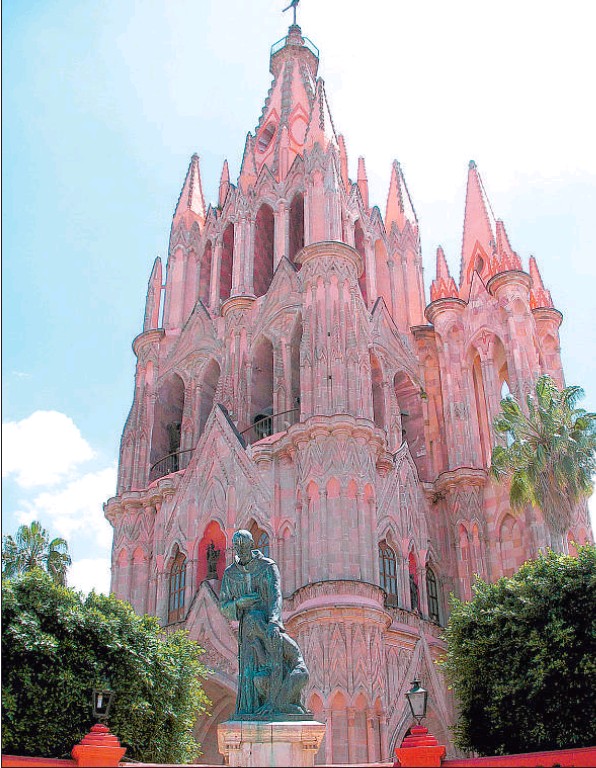

La Parroquia San Miguel, the Disney-esque — or, more accurately, pseudo-gothic — pink church is the centrepiece of San Miguel. BETSY MCNAIR — MY MEXICO TOURS

A luxurious patio at a model home for the Rosewood Artesana project, which will consist of private luxury homes on the edge of a five-star resort.

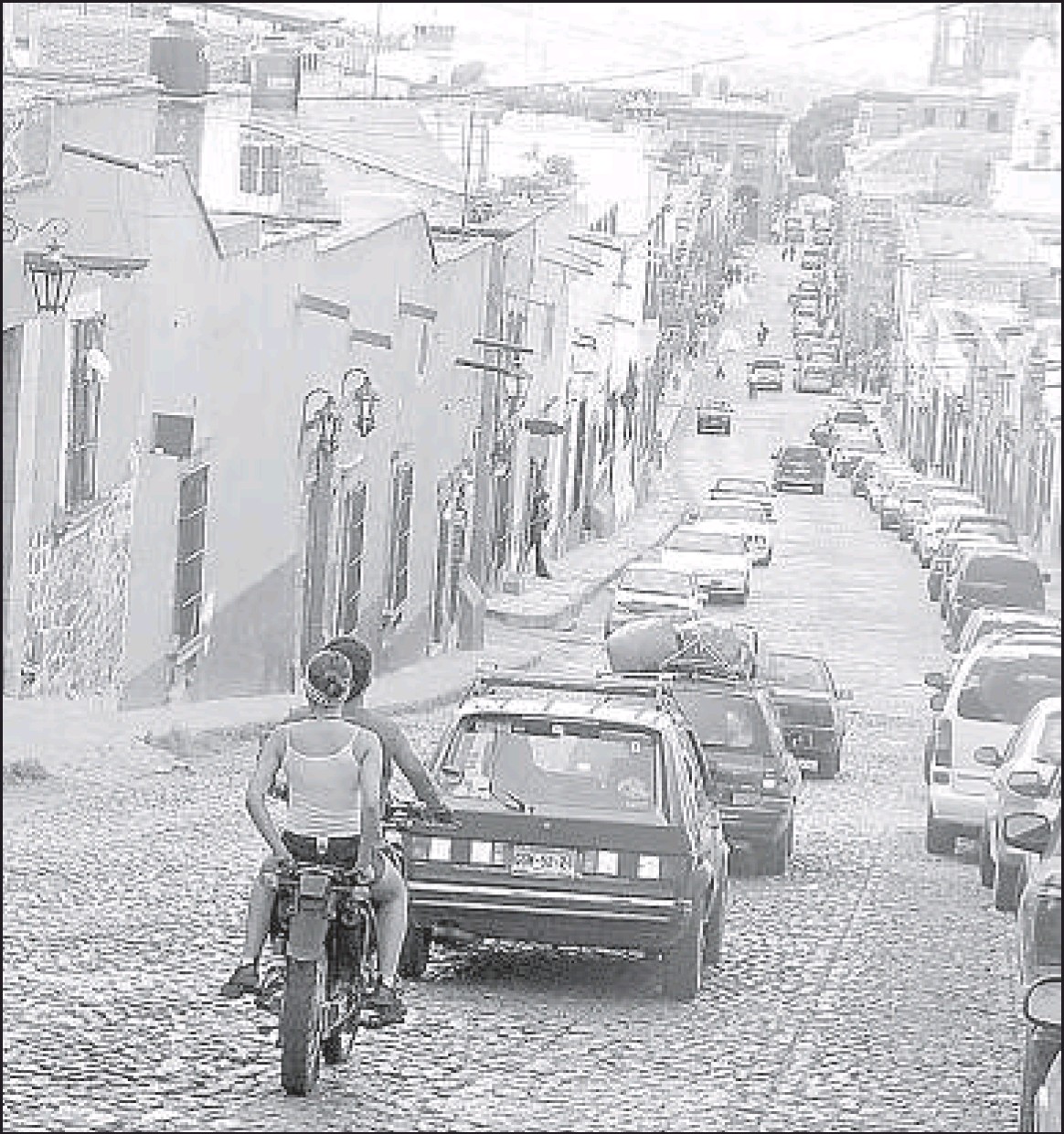

Drivers use the honour system to get around the narrow, cobblestoned streets — where there are no traffic lights. — CANWEST NEWS SERVICE PHOTOS

An old man in a black beret and white sneakers slouches on a velvet couch smeared with daubs of dried acrylic paint. He politely greets his visitors in a living room strewn with framed and unframed paintings, worn furniture, knick-knacks and piles of books and papers. A cat pokes at a plate of unfinished breakfast on an ottoman; boiled egg in a cup, fruit and toast.

The painter leans back and swings his feet up onto the couch to take a look at his unfinished work.

“I think it needs more yellow . . . in the egg,” he says mostly to himself about his painting, tentatively titled “Sir Nobby (the cat) and Breakfast.”

And then, to me, who’s begun to ask a question: “Didn’t anyone tell you I don’t do interviews any more? I’ve said it all. It’s in the books.”

At 97, legendary war artist Leonard Brooks doesn’t have much interest in or need for more fame.

People have been known to come for a holiday and never leave

Commissioned in 1944 by the Canadian government, he made his mark sketching the men working on board the navy’s minesweepers and corvettes.

But for more than half a century, Brooks has lived in the artsy tranquillity of San Miguel de Allende. He is considered one of the early drivers of the colonial city’s lively art scene, along with his late wife Reva, a photographer whose stark black-and-white portraits of rural Mexican life hang throughout the house. (For more stories about Brooks, check out John Virtue’s Artists in Exile in San Miguel de Allende).

Brooks still paints nearly every day, occasionally puts on an exhibit, and will only meet with a Canadian if he feels like accepting visitors. (Brooks is just one of many artists who make SMA their home, including the eccentric Toller Cranston, known to Canadians of a certain age as the Canadian national figure skating champion from 1971 to 1976.)

Brooks and his wife found themselves in this 500-year-old sun-drenched city located on the altiplano (high plain) ringed by the Sierra Madre mountains in the late 1940s, around the same time Second World War veterans were returning home.

Thousands of them were drawn to this city with a perpetual springlike climate, by the thermal springs on the edge of town, and also the fact that their GI education grants could stretch a lot further here than in the United States.

The Disney-esque (actually pseudogothic) La Parroquia San Miguel is the iconic pink-hued parish church that dominates San Miguel de Allende’s historic centre. In its shadow they rebuilt their lives and pursued an education in the arts or music. For Leonard and Reva it became home, where they were surrounded by contemporaries and could pursue their artistic passions. That is with one exception — a temporary deportation from their borrowed city during the Communist “witch-hunting” years of the McCarthy era in the 1950s.

The students might have studied at the Esquela Bellas de Artes (School of Fine Arts), where he taught or at the Instituto Allende. To this day, both facilities attract art, language and music students from around the world and provide residents and travellers alike with art classes, galleries, stages and open-air cafes where patrons while away the hours reading or catching up on gossip with friends.

Just as it did for many war vets, San Miguel de Allende is a place where people come to reinvent themselves, says the man with a distinct American accent as he leads us through the cobblestone streets, while everyone else appears to be either coming or going from the daily outdoor market.

In a past life, Steve Weisberg was a social worker in the United States; now he’s a theatre volunteer, and on this day he’s telling us stories about the bloody battles for independence from Spain, the stories behind the city’s hand-carved doors, and the once-booming silver mining trade, on a walking tour of the historic city centre.

Over and over, I would hear this refrain from expats that SMA–as it’s informally known–is a place where people start life anew, many of whom are retired or have made it their second or new home. There are just as many anecdotes about those who came for a holiday and couldn’t leave the sounds of the celebratory fireworks (there are more than 100 festivals a year in San Miguel), or the clanging church bells, the beauty of the colonial architecture and narrow and crooked cobblestone streets with the profusion of the bougainvillea that spills over the walls that surround the mansions and modest homes.

Many of the homes, painted in yellows, blues, greens and terra cottas, are adorned with ornate wooden doorways throughout the historic district and in the neighbourhoods carved out of a hill called El Monteczuma.

Many have beautiful door knockers in the shape of a bejewelled hand, a dragon, a lizard or a lion.

As to why these transplants fall in love with the city, it could be as simple as the drivers’ honour system, in which cars, SUVs and even ATVs that chug up the hilly, uneven cobblestone streets don’t have to obey traffic lights –because there are none. Or the fact that there is even a San Miguel shoe, invented by an enterprising family so that people could walk without turning an ankle on the rugged streets.

For these reasons and more “everyone falls in love with it,” says Linda Lowry, a writer from Colorado, one of those who came and never left.

Even though there has been a large influx of North Americans, it’s “Mexicanness” has not been erased.

“It’s not a gringo town,” she says, even though 8,000 to 10,000 nonresidents live in the city, designated a World UNESCO heritage site in 2008.

The only nods to the influence of its northern neighbour are the many locals who speak some English and the not-too-busy lone Subway and Starbucks, tucked into colourful stucco buildings, each surrounded by stone courtyards, art galleries, churches (there are close to 300 in the city) or locally owned boutiques.

“It’s the other way around,” says Victor Cortes. “People come here to integrate themselves.”

The many expats I met have immersed themselves in the community, helping or working alongside the locals, volunteering at the orphanages or helping a local family create a lavender farm whose products will eventually be made into soaps and other products at a resort being built in the historic city centre.

So successful was this endeavour, says Lowry, that the wives with whom she helped get the project off the ground were able to bring their husbands back from the United States, where they’d gone to find work.

“They’re coming home to help with the business,” she says, one anecdote that tells me, not only is it the non-residents who can carve out a new life for themselves, but the local residents can, too.

© Copyright (c) The Province