Change is inevitable, but its course will be determined by its champions and opponents – and rhetoric

Bob Ransford

Sun

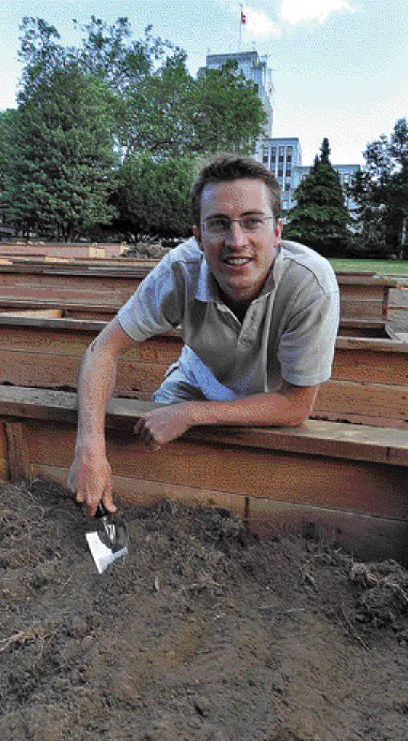

If only there had been a bike or two in this photograph of James Raymond at his garden plot at Vancouver city hall . . . The decision by city council to sponsor a food-producing community garden on the grounds of city hall is one of two decisions, Bob Ransford writes, that symbolically speak of planetary concern, but generate shouts of denial and denouncement. The other is the Burrard Bridge bicycle experiment. Photograph by: Steve Bosch, Vancouver Sun

We need to change the way we live in urban areas in North America if for no other reason than we want to protect the quality of life we have come to enjoy. Recent events in our own backyard demonstrate that we need to ask ourselves how painful we want to make the process of change.

Whether you believe we have to take steps to avert irretrievable climate and ecosystem collapse or you simply believe that mankind’s evolving knowledge has provided us with unprecedented opportunities to reconnect ourselves to nature’s timeless nurturing processes, you are part of a new public consciousness from which action needs to follow.

That action can be painful or painless. A lot really depends on the level of rhetoric and where the push comes from.

If the push for change is controlled by those who want change immediately and wholly or completely, we are in for pain.

Just the same, if the push back in resistance comes from the absolute deniers with loud voices and ugly rhetoric, change isn’t going to come easy.

It is that rhetoric and entrenched polarized approaches to this challenge, in fact, that have generated the minor pain most of us have experienced so far from our efforts to treat our planet and its natural systems with a little more care.

Just think about the Burrard Bridge experiment for a moment. The hysteria that was whipped up in advance of the launch of the project by a few resisters with amplified voices was much more painful to experience than the actual impact of the closure of a lane of traffic in favour of bikes.

The reality is that in dense urban areas we need to broaden the range of transportation choices for a whole range of reasons. Cycling is one of the alternatives to the single-occupant automobile.

This is just one small sacrifice as a step in the right direction, whether it is symbolic or not.

Another clearly symbolic move that seemed to really irk some people was the decision by the Vancouver city council to dig up the lawn at city hall to create a food-producing community garden.

All of the rhetoric around the symbolism — especially from the irked few — ignores the fact that promoting urban agriculture makes sense and causes no harm at a time when we have the knowledge and the natural ability to produce more food locally yet we rely so heavily on imported food.

These are two examples of reasonable strides forward initiated by those with a “progressive agenda.”

Just as I can criticize those who deny the need for change and fight to maintain the status quo with hysterical rhetoric and senseless resistance, I must also take issue with those who are pushing change too fast, too hard and too far.

For change to be effective — which means change accepted as the new norm — it must be incremental.

We’re not all next year going to be floating around the city on eco-friendly hovercrafts made from recycled hemp and powered by the laughter of children.

Change that achieves a reduction in our urban ecological footprint needs to start with symbolic moves followed by deliberate steps in the right direction.

Change is also not going to work if it ignores the realities of the economic system with which we currently generate the wealth that provides for all.

An example of trying to achieve too much change too fast might be the ambitious agenda that was set for the new Southeast False Creek neighbourhood, which includes the Olympic Village.

Those leading the ecological-responsibility agenda were successful in framing this project as a model for a sustainable urban community, but the model may be at risk of becoming anything but.

The green building agenda was pushed to the limit. The range, breadth and quality of public amenities required for the site is a first for Vancouver and likely any other North American neighbourhood. The social agenda included not only a huge commitment to non-market social housing and market rental housing, but also a commitment to pioneering new ideas like urban agricultural in a high density setting.

The fact is that this layering of sustainability initiatives on one project may have killed any chances of the Southeast False Creek neighbourhood being a model anyone can replicate — especially as a private sector project. If the project can only be replicated with deep government subsidies, then it is hardly a model for sustainability.

Aim for incremental change. Keep the rhetoric to a minimum. Celebrate symbolic successes and the kind of change needed to protect the quality of life we have come to enjoy will be achieved with minimal pain.

– – –

Bob Ransford is a public affairs consultant with CounterPoint Communications Inc. He is a former real estate developer who specializes in urban land use issues. E-mail: [email protected]

© Copyright (c) The Vancouver Sun