Residents now have a safe, clean refuge where they once battled bedbugs, cockroaches and dealers

Pete McMartin

Sun

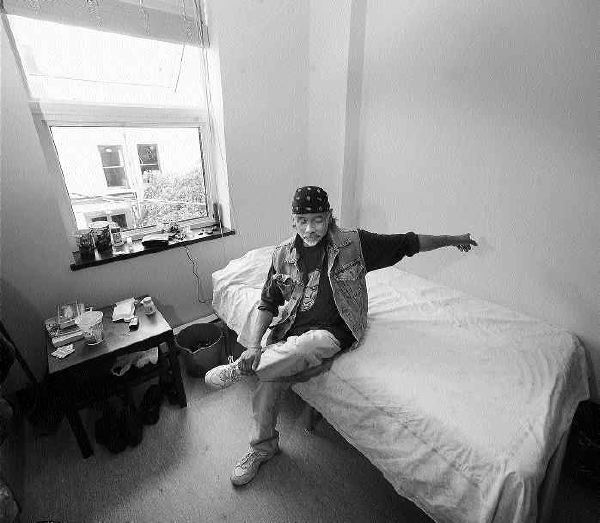

Rocky Wood, 53, is living back in the same room — only much nicer this time around, where he doesn’t worry about someone breaking in or violence in the hotel. Photograph by: Bill Keay, Vancouver Sun

Some of the new features at the Walton Hotel on East Hastings include super-tough wallboard that is hard to punch through, sturdier fixtures and a better security system. Photograph by: Bill Keay, Vancouver Sun

When Rocky Wood lived in the Walton Hotel before its renovation, he slept with a weapon close at hand — a crowbar, a club, whatever.

His room was at the back of the hotel next to a fire escape. The uninvited would try to use it rather than the front entrance. Break-ins were a constant worry. A crowbar was Rocky’s room insurance.

Theft wasn’t the only problem. The Walton was the usual squalid hell common to the neighbourhood’s old hotels. Its happiest tenants were bedbugs and cockroaches. Flooding was common, and the shared washrooms were filthy, when they worked. Addicts, dealers, prostitutes, the poor and mentally ill — the Walton was populated by the socially marginalized. Rocky, himself an alcoholic, sometimes played his own part in it.

“There were a dozen drug dealers in here,” Rocky said. “Sometimes, I’d work the front desk and somebody would come in and they’d say, ‘Hey, I’ll give you a rock if you let my friends in.’ “

Did he?

“Yes, unfortunately, I hate to admit.”

This week, he moved back into the Walton. He got his old room back. It looks nothing like the one he left. His door is a metal one with a secure lock, rather than the wood one that wouldn’t shut right. The walls are unmarked and painted and clean. There is a stainless steel sink where he can do his dishes, and a mini-fridge. He has new plates, glasses, cutlery, pots and pans, even a new toothbrush and toothpaste — all supplied to him as a starter kit when he moved in. The room smells clean.

“I don’t even recognize the place,” Rocky said. “It’s absolutely beautiful. I have more of a sense of responsibility right now because of it. . . . In my old place, it was so bad I didn’t care about how it looked, but I can’t be doing that here. When I get my stuff stored away, I’ll keep it spotless.

“This has given me a breather.”

Whether it gives Rocky a new direction in life is the question the provincial government and taxpayers hope the Walton will answer.

Far-sighted design

In 2007, the Liberal government, under the aegis of BC Housing, bought 10 Downtown Eastside single-room-occupancy hotels with the aim of renovating them for social housing. Later, the province would buy 13 more SROs in the Downtown Eastside, plus several other hotels in Metro Vancouver and up-country.

The province and the City of Vancouver are also developing six new sites on undeveloped properties in the city for social housing. But newly renovated SROs like the Walton are being developed first to preserve the existing housing stock in the Downtown Eastside and to get accommodation for those who need it in the shortest possible time.

These renovated SROs are a new page in the fight against the cycle of poverty in the Downtown Eastside. It is supportive housing with the idea that to break that cycle, residents must first have a stable, affordable residence in which they can feel safe. The hotels will be managed by staffs who know the problems.

There is also a cost-effectiveness factor to the new housing strategy: that the less time residents spend on the street accessing social services, including police, the less in the long run it will cost taxpayers.

The Walton, with 48 units, is among the first of the SROs to go through a major renovation. It cost $4.6 million, or about $95,000 per unit. It reopened earlier this month. Its bare-bones interior disguises the fact that the results are spectacular.

Its interior design is the most fascinating part of the process that went into the renovation. The Walton is housing for what in any other setting would be considered impossible tenants — those with mental, addictive or socialization problems — and its interior was built to (a) take a beating and (b) keep out the scourge of the Downtown Eastside, namely bedbugs.

The man who oversaw its design was James Weldon of BC Housing, who has the unique title of director of construction innovation. Weldon, a Brit, learned his trade doing difficult renovations on the ancient stock of buildings back home.

What Weldon knew was that not just soundness of construction mattered in a renovation of a place like the Walton, but process. Things had to be done right. Details mattered, even details as mundane as baseboards. And the Walton’s baseboards, which appeared unremarkable, did not betray the fact that they were a marvel of design.

“I was the first person to come in here after the purchase,” Weldon said, “and when we tore off the old baseboards and Gyproc, the walls were filled with bedbugs. Just crawling with them.”

Baseboards, oddly, were a key to the problem.

“In typical renovations,” Weldon says, “they put a rubber baseboard on. And the rubber baseboard is a major problem. It’s real difficult to get a tight fit to the wall. And if you try to spray to kill the bedbugs, the bedbugs go behind the rubber.”

Rubber baseboards, which are cheap, not only fail to act as a prophylactic against the bedbugs, they protect the bedbugs against fumigation. Once the bedbugs get behind the baseboards, Weldon says, they get into the walls, and from there, any renovation being done is wasted.

Under budget, and early

Under Weldon’s direction, when the renovating crew rebuilt the walls, they put in a layer of diatomaceous earth with the insulation. The earth is the microscopic skeletal remains of algae-like plants, which have razor-sharp edges that will slice up the bodies of any bedbugs that do get into the walls. And when the baseboards were reapplied, Weldon had them sealed laterally at four different points where bedbugs might find a seam.

“Basically, there’s no way for the bedbugs to migrate.”

Weldon had other precautions built in against infestation. In the hotel’s basement, he is having a sauna room built — not for the tenants, but for their possessions.

High sustained heat kills bedbugs, and the sauna will be large enough, Weldon said, to accommodate even mattresses.

Weldon made it a tough building. The flooring is a vinyl with a matte finish, and it is a continuous membrane that is wax-free, easily cleaned and, Weldon said, “extremely durable.”

Rather than conventional Gyproc, crews put up a super- tough wallboard that is hard to scar or punch through. It also is mould-resistant, Weldon said, important for tenants who have compromised immune systems.

In the old building, Weldon said, tenants would disconnect the fire alarms because they would go off at the slightest hint of smoke. So Weldon had alarms installed that were less sensitive, and had each alarm wired to a central panel in the manager’s office that shows if the alarm has been disconnected. The panel also shows if there is a fire in an individual room, making it easier and faster for fire crews.

He made sure the fixtures such as hallway light fixtures were sturdier than normal. The stainless steel kitchen sinks he installed in the rooms were $190 models from Ikea fitted with levered faucets that run for only 15 seconds, a precaution against flooding.

(Weldon also had central floor drains installed in the hotel’s common washrooms and kitchens to prevent flooding, a constant hazard in the old hotel. There was so much flooding and leakage that a storefront grocer on the ground floor of the Walton installed a trough in his ceiling, and so much refuse and sewage would collect there he would have to empty it with a mop.)

The door locks operate on a security-card system, much like a conventional hotel. The doors, which are metal, are set in reinforced frames. There are security cameras in the hallways. Access to the hotel’s common areas — a community kitchen, a TV room, a small library and a couple of computer terminals — is through locked doors, and staff must be on hand while tenants use those areas.

When Weldon first inspected the Walton, he found a building in much worse shape than first thought. There was rot in major supporting beams. Mould was everywhere. The roof was a mess. He had to find a process to keep costs down.

“For the scope of the work we did,” Weldon said, “we had a system of sequential tendering that allowed us to get tenders in as the worked progressed. That way, we prevented bids coming in that didn’t deal with unknowns. It’s a common thing in the renovation business that when you have to ask a contractor to, say, put in a different type of screw that you hadn’t expected to use, he charges you five times what the screw’s worth. That’s just the way it is. But this way, by identifying the problems as they came up, and taking a hands-on approach, we could be more cost-efficient.”

It took 13 months. The renovation, Weldon said, came in under budget and several weeks early. The process, and what they learned from the Walton, he said, won’t just be transferred to the other SROs being renovated around the Downtown Eastside, but will be made available to private businesses, too. It could make a difference to how renovations are done here in the future.

Whether it makes a difference in the future of the Rocky Woods of the world remains to be seen.

© Copyright (c) The Vancouver Sun