Transformation to unique complex has price tag of more than $10 million

John Mackie

Sun

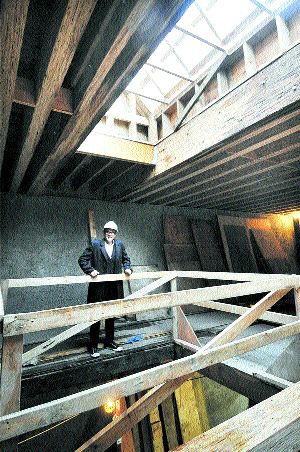

Bob Rennie at one of the light wells featured in the heritage restoration of the Wing Sang building, Chinatown’s oldest. Photograph by: Ian Lindsay, Vancouver Sun

The first thing Bob Rennie wants you to know about his restoration of the oldest building in Chinatown is that it isn’t a condo development, it’s an office and art gallery.

“If it was condominiums it would just get all confused by the community that it’s a real estate deal,” says Rennie, arguably the most successful realtor in Vancouver history.

“It’s a crime of passion. We want a house for the art, and this is where we’re going to put it.”

He could have added “cost be damned,” because his restoration of the 1889 Wing Sang building has proven incredibly expensive.

He doesn’t want to give an exact figure, but admits the project is “100 per cent over budget.” Asked if it’s a $10-million project, he smiles and says “it’s over that.”

Still, he doesn’t seem overly distraught. In fact, he’s quite excited about his four-year transformation of one of Vancouver‘s most historic structures into something unique.

The Wing Sang property at 51 East Pender is two structures, a three-storey building in front and a six-storey building in back. The front building was built by Chinatown patriarch Yip Sang for his import-export business, the Wing Sang Co. Originally two storeys, a third was added in 1901. In 1912, Yip added a six-storey building in back, where he housed his large family — four wives and 23 children.

Together the buildings have 27,000 square feet of space. Rennie plans to use 6,000 sq. ft. in the front as offices, and allocate the rest to his art gallery. It will feature items from his large art collection, but won’t be accessible by the public — it’s a private gallery.

The project should be finished by the fall. It promises to be a dramatic space. The main floor in the front building will have high ceilings, about 14 feet. But that’s small potatoes compared to the art gallery in the back building, where several floors are being removed.

When construction is finished, it will be a four-storey space — 40 feet.

There will be an adjacent space with a 20-foot ceiling in the front building where films and videos will be shown, as well as a rooftop sculpture garden.

“You can park a car on that roof,” says Rennie, 52.

“One of the sculptures is two tons, [so it was rebuilt] to take the weight.”

Rennie is a serious art collector, with works from internationally known contemporary artists like Britain‘s Thomas Houseago (who did the two-ton sculpture), Germany‘s Anselm Kiefer and Vancouver’s own Rodney Graham, Ian Wallace and Brian Jungen.

“There’s about 40 artists we have in extreme depth,” he notes.

“There’s different parts of the collection that have to do with identity and prejudice, there’s a painting collection, there’s sculpture.”

His restoration is a work of art in itself. The architect for the project is Walter Francl, and the heritage consultant is Robert Lemon, but the vision is Rennie’s.

The two buildings are red brick, with wood frames. The front building was in relatively good shape, but the back building had been vacant since the mid-’70s, and was a mess. Pigeons had been roosting there for decades, leaving behind a foot of droppings.

“They had a team with hazmat suits [go in],” says Rennie. “It was unbelievable. We put a rat trap in every room.”

It took a few months, but eventually they cleaned it up. But there was another problem with the back building: because it hadn’t been heated in decades, the brick was in rough shape.

They installed temporary bracing, then poured shotcrete inside the original brick walls to support the structure. With 20/20 hindsight, Rennie says it would have been cheaper to tear down the back building, build a new one, then put a brick facade over top. (The back building was condemned when he bought it.)

He offset some of the costs by selling off $4,850,000 in heritage density bonuses to the Jameson House development downtown. But the cost was far higher than the money he received.

He shrugs. “But it’s done now, that’s all water under the bridge.”

The ground floor of the front building will be occupied by Rennie and Associates, the retail wing of the Rennie empire (it does condo resales). Rennie Marketing, which deals with new condo developments, will be on the second floor. Rennie’s own office will be on the third floor.

“I’ve never had an office before,” he says with a laugh.

“I share a round boardroom table with four other people. I do not have a computer. Yet. I’m going to get one. I do everything on a BlackBerry, and Kevin who runs the office enters everything. But I’m going to have an office.”

The heritage gem of the project is the boardroom on the third floor. It was a schoolroom for Yip Sang’s children, and is virtually unchanged since it was built in 1901, with beadboard wainscotting on the walls and ceiling and a large blackboard with ancient writing.

“[Yip Sang’s son] Henry said those are bowling scores from 70 years ago,” marvels Rennie.

“Through all of the controversy, all the vacancies, it seems everybody’s always had a respect for this room. The writing stayed, nobody abused it.”

The rest of the building has been more or less stripped down to the bare walls and rebuilt, but the schoolroom is being saved as is. They aren’t even going to paint it.

“We decided to just scrub it and clean it,” says Rennie. “Put in contemporary furniture, and just let it live the life it has.”

There used to be an alley between the front and back buildings, but it has been covered by a glass roof. The ground floor of the back building is parking, so visitors will walk up some stairs to the gallery, which will have an arched entrance 24 feet high.

The roof should be quite cool. Birch trees will be planted along the east side, and poppy plants on the west and north, a reference to the opium trade that flourished in Chinatown before it became illegal in 1908. Yip Sang, in fact, imported opium into the building. (Yip’s main job was working with the Canadian Pacific Railway — he brought thousands of Chinese workers into Canada to build the CPR.)

There will be one piece of art the public will be able to see — a 75-foot-long neon sign by Britain‘s Martin Creed that will be placed along the top of the back building.

“It says ‘Everything is going to be all right,’ ” Rennie says.

“It has a lot of meanings, looking at the challenges in the area and the challenges in the economy. You’ll see that in the Olympic Village.”

Rennie is well aware Creed’s statement may provoke some controversy, given its location near the long-troubled Downtown Eastside. But the life-long Vancouverite purposely bought in the neighbourhood rather than downtown, because “I wanted to be part of the new vision for the Downtown Eastside.”

The first building he tried to purchase was the old Blue Eagle restaurant on East Hastings. It wasn’t available, so he bought the Wing Sang building for $1 million. It was a quick deal — he was told he could buy it if he put the money up that day, so he did, without ever setting foot inside.

He’s an interesting fellow. The day we met, he was trying to get hold of Premier Gordon Campbell’s cell number so he could talk to him about the Olympic Village site, where Rennie is selling the condos.

A few minutes later, a street person came up and asked if Rennie could charge his cell phone in his car lighter.

Rennie obliged, and talked to the guy about his life on the streets for about 10 minutes. Then he gave him back his charged phone, along with a $5 bill “to go get some lunch.”

Rennie has no interest in moving the down-and-out from the area.

“My goal is to balance the street, with the fortunate and less fortunate walking together,” he says.

“If you’re moving into this area, you’re buying into diversity.”

© Copyright (c) The Vancouver Sun