Paul Davidson

USA Today

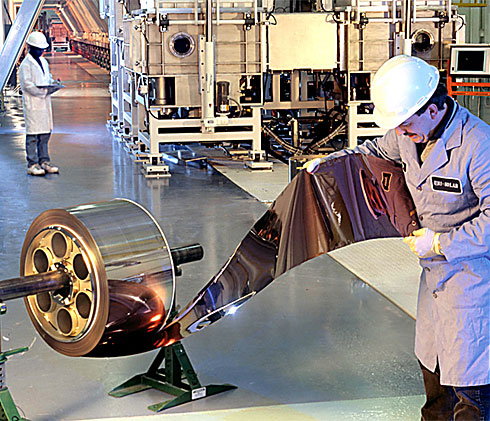

United Solar Ovonic makes solar-absorbing material that can be pasted on roofs at low cost.

Solar power has long been the Mercedes-Benz of the renewable energy industry: sleek, quiet, low-maintenance.

Yet like a Mercedes, solar energy is universally adored but prohibitively expensive for most people. A 4-kilowatt solar photovoltaic system costs about $34,000 without government rebates or tax breaks.

As a result, solar power accounts for well under 1% of U.S. electricity generation. Other alternative energy sources, such as wind, biomass and geothermal, are far more widely deployed.

The outlook for solar, though, is getting much brighter. A few dozen companies say advances in technology will let them halve the price of solar-panel installations in as little as three years. By 2014, solar-system prices will be competitive with conventional electricity when energy savings are figured in, Deutsche Bank says. And that’s without government incentives.

If that happens, solar panels would become common home and business appliances, says Brandon Owens of Cambridge Energy Research Associates.

Innovations — led by semiconductor firms and a new crop of “thin-film” solar makers — wring more power from sunlight, use less silicon to make panels and make factories more efficient.

Venture-capital firms pumped $264 million into solar companies in 2006, up from $64 million in 2004, research firm Clean Edge says. The start-ups also have benefited from $159 million in U.S. research grants this year, largesse from efforts to reduce power plants’ global-warming emissions.

Sharp price swings

High costs of solar panels have been due to volatile silicon prices, low production volumes and high setup costs.

Solar panels generate electricity when photons in sunlight knock loose electrons in silicon — the same material used in PC chips. The silicon is sandwiched between two metal plates; electrons flow from one to the other.

Several years ago, SunPower, a unit of Cypress Semiconductor, (CY) realized the top metal plate was reflecting the sun’s rays, cutting efficiency by reducing the percentage of sunlight converted to electricity. So the company decided to put both plates beneath the silicon. It now has an industry-high efficiency of 22% vs. an average of 16%, says analyst Dan Ries of Monness, Crespi Hardt & Co. That means fewer panels are needed to produce power, shaving installation costs and making systems more affordable for homes, which have smaller roofs than most commercial buildings.

SunPower, which says it will earn about $90 million on $740 million in sales this year, expects its prices to be competitive with grid power by 2012, says Vice President Julie Blunden.

Also poised to stir up the market is Applied Materials, the No. 1 producer of machines that make computer chips. It charged into the industry last year by paying $464 million for solar maker Applied Films. Now, it’s transferring to solar the efficiencies it brought to flat-panel TV and laptop manufacturing. Its machines carve an ultra-thin solar cell into a giant, 55-square-foot sheet of glass to slash production and setup costs.

“We want to get demand going,” says Applied CEO Mike Splinter.

Like wind power, solar energy is spotty, working at full capacity an average 20% to 30% of the time. Solar’s big advantage is that it supplies the most electricity midday, when demand peaks. And it can be located at homes and businesses, reducing the need to build pollution-belching power plants and unsightly transmission lines.

In states such as California, with high electricity prices and government incentives, solar is already a bargain for some customers. Wal-Mart recently said it’s putting solar panels on more than 20 of its stores in California and Hawaii. Google is blanketing its Mountain View, Calif., headquarters with 9,212 solar panels, enough to light 1,000 homes.

Burning demand

The solar industry is expected to triple in the next three years, from about $13 billion to $40 billion in revenue, says analyst Jesse Pichel of Piper Jaffray. Turbocharging sales are government incentives in countries such as Germany and Japan. In the USA, generous customer rebates in California and New Jersey — by far the largest U.S. solar markets — along with a federal tax credit have trimmed system prices by a third or more.

Most states don’t offer solar rebates, but prices still have fallen about 90% since the mid-1980s — 40% annually the past five years — as surging sales have led to cost efficiencies, says Rhone Resch, head of the Solar Energy Industries Association. Now, experts say it will take a quantum technological leap to quickly lower prices to utility levels. An armada of companies say they are poised to do just that:

•Traditional solar makers. This group, which includes SunPower, relies on standard silicon wafers as a semiconductor. They make up more than 90% of the solar industry. Some are using less silicon, because electricity is produced only in the top layer.

Evergreen Solar uses two ribbons to finely shape molten silicon. Others cut silicon into wafers, losing up to half insilicon sawdust. Evergreen’s method eliminates the waste.

Sharp, the No. 1 manufacturer, takes a different tack, slashing setup costs by bundling panels with racks that attach them to roofs.

•Concentrating photovoltaic makers. They use lenses or mirrors to magnify sunlight. SolFocus‘ mirrors concentrate sunlight 500 times, letting them use a fraction of the semiconductor found in standard panels. But the systems don’t work on cloudy days and require cumbersome trackers to follow the sun, making them suitable only for utilities and big industrial customers.

•Thin-film manufacturers. They have achieved the lowest costs by layering 1% of the semiconductor in regular panels on sheets of glass. They often use material that’s cheaper than silicon. That’s a big advantage, because a worldwide silicon shortage has pushed up prices. First Solar’s (FSLR) production costs are $1.19 per watt of generating power vs. $2.80 for traditional solar systems. It says it will hit about $1 a watt, the price of building conventional power plants, by 2010. The start-up has contracts for $4 billion through 2012.

Another start-up, Nanosolar, embeds tiny semiconductor particles in ink, helping it churn out panels as easily as a printing press. And United Solar Ovonic deposits its semiconductor on flexible sheets of stainless steel that look like rolls of film and can be pasted on roofs at low cost.

One caveat: Thin-film panels are about half as efficient as standard systems. Thus, they need more space and are mostly geared to utilities and businesses.

Owens cautions that reaching grid-like prices could take longer than solar makers vow. States with more sunlight and higher power rates could get there sooner. Makers “have been promising the moon for a long, long time.”