Capitalism is alive and well, despite dire predictions to the contrary

Miro Cernetig

Sun

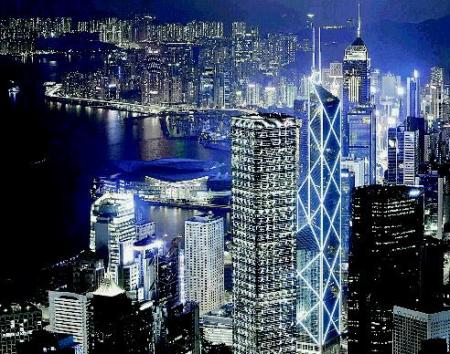

The hypnotizing skyline of modern Hong Kong is dominated by the imposing and symbolic Bank of China building. Photograph by : Reuters

Boats pass by Shanghai’s skyscrapers in the showcase Pudong financial district. Photograph by : Reuters

HONG KONG – If anything symbolized the jitters surrounding China taking over Hong Kong a decade ago (on July 1, 1997), it was the urban legend surrounding the 369-metre, silver phalanx constructed by the Bank of China.

It was said the austere skyscraper, with its windows of silver mercury that let Chinese bankers see out but nobody in, had been deviously designed by a Communist-friendly feng-shui master. Its dagger-shaped corners would supposedly rain negative energy down upon British-ruled Government House, the epicentre of colonial power, a sort of invisible Chinese death ray to neutralize Hong Kong’s colonial overseers and their evil capitalist ways.

It was a good story, and a perfect metaphor capturing the zeitgeist of “The Handover” — when the People’s Liberation Army was about to roll in from across the Chinese border to take over Hong Kong 160 years after China’s rulers lost the Opium War.

This tiny capitalist city-state of seven million was doomed, the conventional wisdom held, to become just another Chinese city. The old, British Hong Kong, with its ultra-rich tycoons and impeccably connected British bureaucrats and bankers clad in Saville Row suits, could not survive for long under the vengeful grip of a nation whose ethos was created by Chairman Mao.

Some heavy hitters staked their reputations on that theory, including Fortune magazine. Its doomsday article, “The Death of Hong Kong,” is still not forgotten here.

Oh, the old British colony might remain a regional business hub, a convenient shipping and business port into China, Fortune sniffed. But its ambitions as a world financial centre? Kaput. It would surely shrivel under the Communist regime’s authoritarian grip.

“What’s indisputably dying,” declared Fortune, “is Hong Kong’s role as a vibrant international commercial and financial hub — home to the world’s eighth-largest stock market, 500 banks from 43 nations, and the busiest container port on Earth. What will change after midnight on June 30, 1997? Everything.

“Within months of the transition to Chinese rule, the now dominant use of English, the universal language of business, will give way to far more extensive reliance on Cantonese and Mandarin,” Fortune decided. “Troops of the People’s Liberation Army, which has already formed links with the powerful local criminal gangs known as ‘triads,’ will stroll the streets. From Beijing, whichever faction emerges on top in the post-Deng Xiaoping struggle for power will control every branch of Hong Kong’s government — replacing elected legislators with compliant members, selecting cooperative judges, and appointing the chief executive.”

Scary stuff, some of which also prompted hundreds of thousands of Hong Kong residents to seek other passports, many of them to get into Canada. But a decade later, Fortune’s crystal ball-gazing seems hopelessly inept.

“Fortune was wrong,” says James Tien, the leader of Hong Kong’s pro-business Liberal Party, who serves as an elected member in the former colony’s legislative council. “Look around you. Things still work. Hong Kong is still here.”

Indeed, as the Brits might say.

On a macroeconomics level, Hong Kong’s bottom line looks pretty good: The Hang Seng, the stock exchange that is now a bellwether of both China and Asia’s financial health has been booming. It hit above 22,000 points earlier this week, a record that many predict will be broken again.

The local real estate market is once again nearing the stratosphere. And the international bankers and financiers haven’t been in as festive a mood since before the handover. Last year, more IPOs were done in Hong Kong than Wall Street, meaning lots of big bonuses and a run on luxury cars.

The only downside in terms of figures, notes Tien, is that the per-capita income is still about $27,000 US, roughly what it was a decade ago. It is largely high-end real estate, owned by the foreign bankers and those of the tycoon class and their ilk, that is booming.

“Still,” says Tien, “Fortune was wrong. Hong Kong is doing pretty well.”

That is also the conclusion of James Forder, the Oxford economist and author of Hong Kong, Ten Years On, a report commissioned by the powerful business group John Swire & Sons Ltd.

“For many businesses, Hong Kong is now a more attractive place than it was when under British control,” Forder concludes in his independent study. “The old business conditions have largely been retained, but the Hong Kong economy is now better integrated with the Chinese, and the rapid development of that country makes for a huge additional opportunity.

“The ‘One Country, Two Systems’ approach to maintaining the capitalist system in Hong Kong has been almost completely successful. Despite the reversion to Chinese sovereignty, in Hong Kong it is business as usual.

“Capitalism remains alive and well, and just as welcoming to the foreigner as it has ever been. . . . Hong Kong is blessed with just the right separateness from China to maintain strikingly superior institutions, but just the right kind of integration to make use of them to the full.”

The question, of course, is what happened to Shanghai? Another theory that reigned supreme a decade ago was that the Communist regime was intent on eclipsing Hong Kong as the star of high finance in southeast Asia.

Billions off dollars had been pumped into Shanghai, to bring it back to its glory days before the 1949 Communist revolution. There were new elevated roadways, a profusion of five-star hotels, a massive new stock exchange and, most tellingly, Pudong. Almost overnight, central planners had turned the rice paddies and villages on the other side of the Huangpu River into a massive real estate development that was to be China’s gleaming version of Manhattan.

Shanghai’s destiny to replace Hong Kong seemed further assured by the events that rocked the former British colony to its core after the handover.

Within days of the Union Jack coming down, the Asian currency crisis hit, causing the Hang Seng to plummet. Then there was the worldwide burst of the tech bubble. Then came a plunge in real estate, a bird flu scare, and then the deadly Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), which started just across the border in Guangdong and spread to Hong Kong, causing foreigners to stay away. At one point, the famous Peninsula Hotel had only six guests.

“It was like something out of the Bible,” recalls Mike Rowse, Hong Kong’s director-general of investment promotion. “It seemed we were being hit with everything that could possibly happen.”

But Rowse now says Hong Kong — positioned on China’s edge at a time when that country is booming, and sitting on $1.2 trillion US in foreign reserves that grow by the day — is joining London and New York as one of the world key financial centers.

It’s a view that is heard often these days in Hong Kong, and it’s largely fueled by one fact: Shanghai, despite its ambitions, has profound limitations. While it may have begun to look a lot like Hong Kong on the surface, it still remains Chinese: Its financial system is based on the renminbi, meaning it lacks a fully convertible currency; the city still has a paucity of English speakers; and, perhaps most troubling of all, it suffers from endemic corruption that seems to go to the highest levels.

“What caused the reversal of fortunes? Shanghai wasn’t ready for the big-time,” concluded a recent analysis by the Wharton business school. “Its financial services companies — typically state-run — and stock brokerages were unsophisticated. Shanghai stock brokerages went bankrupt after promising returns on stocks that tanked. Big-money investors weren’t comfortable with weak accounting rules and Chinese market regulation.”

Also, Shanghai fared poorly in the shift in Beijing’s national power structure. Former President Jiang Zemin and Premier Zhu Rongji — both previously Shanghai mayors — had a sweet spot for the city and a desire to see it restored to its status before the revolution as China’s financial hub.

But current President Hu Jintao has no such political powerbase there, and many think he seeks to reduce the influence of Shanghai’s top officials as he consolidates his rule. In fact, China’s leader seems to be taking a deep interest in anti-corruption measures in Shanghai.

“A political backlash in the form of an investigation into local corruption has snared local political bosses,” notes the Wharton analysis. “In September, [2006], the central government fired Shanghai Party Secretary Chen Liangyu for his alleged involvement in the mismanagement of the city’s social security fund. Many others are being investigated.”

That scandal has set Shanghai’s international reputation back, and helped Hong Kong cement its status as one of the world’s best and most-regulated places to raise capital.

Even China’s “red chip” companies seem to agree. Last October, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China floated the largest IPO of the year, raising $19 billion. Hong Kong’s share of that pot was $13.9 billion; Shanghai raised just $5.1 billion.

That trend is likely to continue for years to come. In 2003, foreign direct investment into Hong Kong was $13.6 billion. Last year, it was $42.9 billion. And in the first quarter of 2007, $15.4 billion has already flowed in, suggesting another record year ahead.

Positioned on the edge of China, between the west and east, Hong Kong is also likely to be further bolstered by the mainland’s desire to become a more aggressive player on the world stock exchanges. Just this week it announced that a new investment agency would be getting $200 billon US to invest in foreign ventures, much of which will likely flow through Hong Kong.

Canada’s man on the ground in Hong Kong is Consul General Gerry Campbell, a veteran diplomat who came to the colony 30 years ago and is now on his third posting here. He reckons that, aside from Hong Kong’s deeply ingrained culture as an international financial centre, what the doomsayers missed when they predicted its eclipse by Shanghai was the nature of China’s economic transformation.

“Hong Kong is riding on the China wave economically,” he said, sitting in an office that overlooks Hong Kong’s busy harbour. “That’s what few people foresaw.”

Canada, while certainly not in the league of the biggest players in Hong Kong, seems to be holding its own.

The latest figures show Canada received $6.3 billion in foreign investment from Hong Kong in 2005, while Canadian companies invested $3.8 billion into the city. The Canadian consulate estimates 15 Canadian companies have regional headquarters in Hong Kong, another 29 have regional office, and that there are about 150 Canadian companies with some sort of offices.

But Campbell, who is from Vancouver and sits in front of a painting that shows our city’s harbour, agrees that more inroads could be made by Canadian business. There are, according to recent estimates, about a quarter-million Hong Kong residents with Canadian passports. They form a network of potential business partners, about 3.4 per cent of Hong Kong’s population, yet to be fully explored.

“That’s where I think we haven’t made the link,” said Campbell, although he added more efforts are underway to connect Canadian businessmen with their compatriots.

Bernard Pouliot, the chairman of the Canadian Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong, whose 1,000 members make it the largest outside of Canada, has spent 29 years in Hong Kong. He agrees the former British colony has emerged as China’s business capital, and urges Canadian small- and medium-size businesses to look to Hong Kong as the launching point into China. That, he says, is easier than before 1997, because 10 years after the handover, after enduring their repeated crises, Hong Kong’s business players are more down to earth and open to joint ventures with outsiders.

“In the 1990s, these guys were rolling in gold,” said Pouliot, who runs the financial services company Quam. “They thought, ‘Why do I need China? Why do I need anyone else? We’re doing great.’ But the Asian financial crisis and SARS, well, it humbled them.”

“Hong Kong is New York, it’s the place to be,” he said. “Shanghai is okay, too, but is more like Chicago or Los Angeles.”

But he offers a caveat: “This will change in time. Shanghai will become China’s New York. Hong Kong more like Chicago or L.A.”

How much time?

“Ten, maybe 15 years,” he estimates. “Hard to say. But it will happen. That is what the Chinese want.”

One thing that won’t be disputed, is that if China’s boom continues there will be enough wealth and financial deals for both Hong Kong’s and Shanghai’s financiers to share.

Hong Kong’s destiny may be to be another Chinese city, but it will be one of the richest.

HONG KONG’S FORTUNE

Fortune magazine, writing just prior to the July 1, 1997 handover of Hong Kong to Chinese sovereignty, warned of calamity. How wrong it was.

“Within months of the transition to Chinese rule, the now dominant use of English, the universal language of business, will give way to far more extensive reliance on Cantonese and Mandarin. Troops of the People’s Liberation Army, which has already formed links with the powerful local criminal gangs known as ‘triads,’ will stroll the streets. From Beijing, whichever faction emerges on top in the post-Deng Xiaoping struggle for power will control every branch of Hong Kong’s government — replacing elected legislators with compliant members, selecting cooperative judges, and appointing the chief executive.”

The city, in fact, suffered far more in the coming years from the Asian currency crisis, the tech-bubble collapse, and the SARS outbreak. But Hong Kong has recovered, and is again a leading engine of economic growth for the entire Asia-Pacific region.

PEARL OF THE ORIENT

Hong Kong’s economy, especially its financial services industry and role as a regional corporate centre, rivals that of most countries:

– GDP: $189 billion US in 2006 (6.8% growth over 2005)

– Per-capita GDP: $27,500 US in 2006 (compared to $38,888 in Canada)

– Total exports: $315 billion US in 2006 (up 9.4% over 2005)

– Total exports to Canada: $1.59 billion in 2006 (up 11.1% over 2005)

– 15th-largest Canadian export market ($1.59 billion in 2006)

– In 2007, Hong Kong will raise more money through IPOs than London or New York

– Second largest stock market in Asia (after Tokyo)

– Largest investor in mainland China

– Ranked as world’s freest economy every year since 1970

– World’s busiest airport (in terms of international cargo)

– World’s second-busiest container port

© The Vancouver Sun 2007