Stingray populations explode with the demise of great sharks

Margaret Munro

Sun

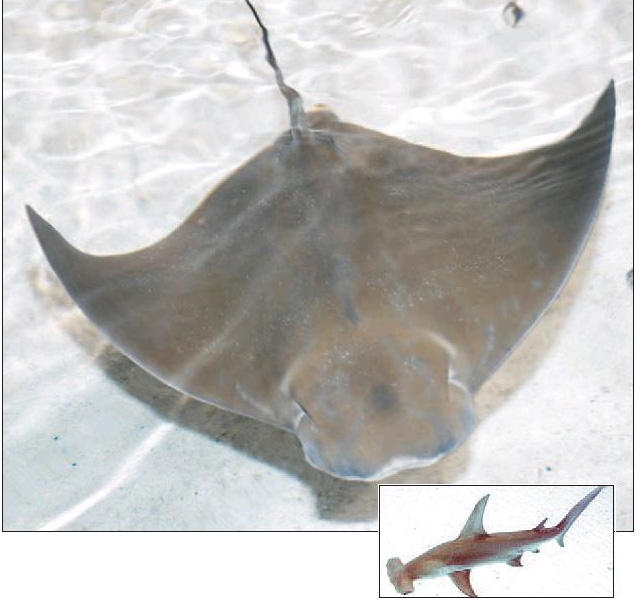

Cownowe rays are cruising the Atlantic coast wiping out scallop beds and threatening oysters and clams. Meanwhile, great hammerhead sharks are on the decline. PEW INSTITUTEOF OCEAN SCIENCE.

Huge schools of cownose rays, metre-wide creatures with poisonous stingers on their tails, are cruising the Atlantic coast in unprecedented numbers, wiping out scallop beds and threatening oysters and clams.

And half a world away in Japan, the population of longheaded eagle rays has exploded and is devastating lucrative wild and farmed shellfish beds, according to a Canada-U.S. research team that has linked the soaring number of rays with the demise of the great sharks.

“Lopping off the top predator has had some completely unforeseen consequences,” says marine biologist Julia Baum of Dalhousie University, co-author of the study published in the journal Science today.

She and her colleagues show huge declines in large predatory sharks, such as the great whites and hammerheads, have corresponded with an explosion in the number of rays, skates and other creatures the sharks used to keep in check.

The most dramatic example is the cownose ray, which the scientists estimate is now close to 20 times more common than it was in 1970s.

An estimated 40 million cownose rays now migrate up and down the Atlantic coast in tight, hungry schools. “They pack in side-to-side, and stacked like sardines,” says Baum.

Or as Charles Peterson, a marine biologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, puts it: “They look like a starship fleet on some sort of fantastic space voyage” as they migrate up and down the coast.

He says the rays have wiped out North Carolina’s bay scallop fishery, which has been closed for three years, and have been destroying oysters and clam beds. They have taken to digging into the seafloor with their long, pointed pectoral fins to get at buried shellfish. In the process, the rays are destroying seagrass beds that are a critical nursery for many fish and shellfish species.

Cownose rays are hard to miss as they migrate through shallow coastal waters. But the researchers say their population boom is just one example of the ecological “distortion” caused by the loss of the sharks — a distortion they believe can be only corrected by protecting the great sharks, which are killed by the millions each year.

The new study, based on detailed fisheries surveys from the eastern seaboard dating back to 1970, shows that there have been sharp increases in the populations of 12 species of rays, skates and small sharks that used to be heavily preyed on by large sharks.

Baum says little is known about the biology, travels and diets of most of the creatures.

Baum and Ransom Myers, lead author of today’s report who died this week in Halifax, made headlines with a 2003 report that showed the great sharks are in steep decline.

Shark fins are highly valued in Asian markets. The fabled predators also are killed as by-catch in the tuna and swordfish fishery.