John Mackie

Sun

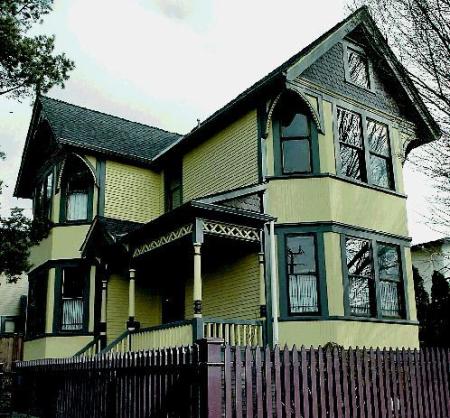

Graham Elvidge and Kathleen Stormont have restored an 1899 home on Vancouver’s Dunlevy Street. Photograph by : Ward Perrin, Vancouver Sun

The extra-large windows and ceiling heights (as in the restored living room) gave plenty of light in Vancouver’s pre-electricity era. Photograph by : Ward Perrin, Vancouver Sun

The ‘almost ecclesiastical’ millwork on the newel post and doors helped convince Graham and Kathleen that the house was for them. Photograph by : Ward Perrin, Vancouver Sun

The ‘almost ecclesiastical’ millwork on the newel post and doors helped convince Graham and Kathleen that the house was for them. Photograph by : Ward Perrin, Vancouver Sun

To most people, the old house at the corner of Dunlevy and Prior would have been a teardown. The exterior hadn’t been painted in decades, and the interior was more or less trashed.

“There were literally bullet holes in the walls where the old guy that lived in here used to shoot at the rats,” says Graham Elvidge. “He’d sit there with his .22 and shoot at the rodents.”

Most people would have recoiled in horror at the thought of buying such a place. Not Elvidge. Having an architecture degree, he understood that ‘neath the decrepit surface, the house was still in good shape. And so Elvidge and his wife Kathleen Stormont purchased the home in June, 2004, for $300,000, and set about restoring it.

On Feb. 19, their efforts netted them the Award of Honour at the City of Vancouver’s Heritage Awards — the city’s highest heritage accolade.

Boy, do they deserve it.

The couple has taken a house that Herman Munster would have been scared to step into and made it into a heritage showpiece. To do so they had to overcome some daunting obstacles: The loss of their copper plumbing pipes in a break-in, the theft of all their tools when their vehicle was broken into, and a bizarre accident where a teenager lost control of a rented $100,000 sports car and drove it into the house.

Oh, and we shouldn’t forget about the decades of dog urine that had seeped into the floor. The previous resident had several pooches that apparently did their business in the house for years.

“When a dog [urinates] on the floor three times a day for 50 years — oh, the things you learn — what ends up happening is the moisture evaporates, but the uric crystals stay behind,” explains Elvidge.

“So, the board ends up with this incredibly high kind of saline content in it. What happens is that whenever the humidity rises, moisture is attracted to that highly saline board. So the humidity would rise and we’d end up with these wet patches that would bloom out of the floor and reactivate this ancient [urine].

“We used that as a means of mapping the floor. Before we took the floors up, we did like a police body line, spray painted this body line around the grim zones.”

The couple then took up the floor and did a “sniff test” to figure out which boards stunk. They cut out the offensive bits and were able to reuse 60 percent of the floor — saving a lot of money, because old-growth Douglas fir floors are worth a fortune.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

Their house was built in 1899, when Vancouver was only 13 years old, the population was about 20,000 and Prior street was on the False Creek waterfront (the eastern part of False Creek was filled in for railway lands from 1916-20, pushing the water back to its current boundary).

It’s one of the few local examples left of a Queen Anne home, an ornate Victorian style featuring exterior details like fish scale siding, gingerbread trim and semi-circular “knee brace” brackets over the upstairs windows.

It was built by a man named Frederick Sentell, whose family was one of early Vancouver’s premier builders — the Sentells built Vancouver’s first city hall on Powell Street. In the 1920s it was purchased by the Winchcombe family, who owned it for eight decades.

Elvidge and Stormont had been looking for a house for several months, and been outbid several times, when they found out the Dunlevy house was for sale. They knew it well, because it’s in the historic Strathcona neighbourhood just east of the Georgia Viaduct.

“Anybody who grew up in Vancouver knows this house,” says Elvidge.

“When we saw it was up for sale, we literally turned to each other and said ‘Oh my God, it’s that house.'”

The house was in rough shape, but was all original.

“It had never been renovated,” says Elvidge.

“We couldn’t believe it. When we first came by and looked at the house, our jaws just dropped. Not to mention our noses, because it stunk in here. But the visuals were just amazing, it totally seduced us.”

When he says it was original, he means it. The house had one layer of wallpaper in each room, the layer that had been put on in 1899. The floors had linoleum carpets (linoleum designed to look like an area rug). The baseboards, moulding and plaster and lathe walls were all intact.

The kitchen appeared to be an early 1900s addition off the north side of the house, which is also where the house’s only bathroom was located. Incredibly, there was no plumbing in the original house, which was probably built before the city’s water system reached the street.

The electrical had also never been updated.

“The electrical that was in the house was all surface mounted,” says Elvidge.

“A couple of tiny little wires coming into the house, the common and the hot, single phase 30 amps. Couldn’t have even run a fridge on it I don’t think without blowing the main breaker. And that was it, just surface mounted.

“The house was never plumbed, never had any sewer in it, and never had any proper electrical system in it. It was weird. We were the first ones to ever drill the walls for that stuff.”

Elvidge decided to make the house restoration his job, and spent two years on the project.

“We’re kind of the poster children for sweat equity,” he laughs, estimating that the couple and their friends and family have spent 8,700 hours renovating the house.

If they had paid someone to do the reno, he thinks it would have cost about $300,000. But by doing it themselves, it cost about $70,000.

“If you had to pay somebody else to do it, they never would have done it to the standard that we did it,” he says.

The first thing they did was to lift the house up and fix the foundation. The roof had been leaking, so it was replaced, as was the plaster and lathe walls. The floor came out, was refinished, then reinstalled. So were all the baseboards.

Many contractors save money on such extensive renos by using cheap wood or a substitute like MDF. But Elvidge is a perfectionist, and scoured demo sales for replacement Douglas fir floors and siding.

“With this house you want clear grain Douglas fir for anything you’re doing, it’s wrong to use any other material,” he says.

“We looked for free salvage wherever we could get it. We would change the construction to fit whatever was happening at the time. Typically the salvage is ‘This house is being torn down tomorrow, come and get what you can.’ So you have to shut down whatever else you’re doing and go and do that.”

A good example is the siding, which he took off the old Varsity Grill on West 10th with two friends shortly before it was demolished.

“They were tearing it down, so we peeled the siding off of it, beautiful old Douglas fir siding,” he recounts.

“We ran all that through my friend’s surface planer, he has a millwork shop, ripped all the old paint off. Then we pre-primed it on all sides and put it all back up. This Douglas fir lap siding, you can’t buy that stuff for love or money. I figure we got $5,000 to $10,000 worth of siding for six hours work, 18 man hours.”

He tried to keep the design of the house as original as possible, but did make some changes. He ripped the kitchen addition off, then knocked down a wall between the parlour and dining room to make one continuous space. The dining room then became the kitchen, and the parlour the dining room.

He then took one of the three bedrooms upstairs and divided it into a bathroom and walk-in closet. The closets for the other bedrooms backed onto each other at the head of the stairs, so he got rid of them and made a landing, adding a window for light.

Loads of natural light is one of the features of the house. The downstairs has nine-and-a-half foot high ceilings, and there are two-storey bay windows on both sides of the home.

“There’s a few things about old buildings that made a lot of sense,” he says.

“It was all about light and ventilation. This was just on the edge of getting electricity to Vancouver, so there was still the idea that you would want big tall windows and big high ceilings to bring lots of light into the building.”

There is some amazing millwork in the house, none more so than the elaborate newell post on the stairs.

“I’ve never seen anything like it,” says Elvidge.

“It’s weirdly ecclesiastical. That alone just about sold us on the house, it’s such an incredible piece. [But] it used to scare the living [daylights] out of me. It roughly has the proportions of a woman, about five foot five, and I’d be working away and turn around and go ‘Whoa! Who the hell is in here?’ And it would be the newell post staring me down.”

Above the stairwell is a vintage multi-tiered commercial light fixture, which is often called a butcher’s light because it used to hang in turn of the century shops.

“That came from the old Vancouver courthouse,” says Elvidge.

“Because this is one of those houses that everybody’s seen forever, it had a certain amount of notoriety. This man and his brother were the demolition contractors for the courthouse in the ’70s when it was being converted to the art gallery. At that time all this beautiful old Edwardian stuff was just being chucked in the bin, so they saved a few things. This sat in a basement for 30 years; he thought this would be a good place for it to land.”

All sorts of people dropped by during the renovation to offer odds and sods, or just encouragement. The masses seem to love the house at Dunlevy and Prior as much as Elvidge and Stormont; they were happy that someone would fix it up.

“I think most people are a bit horrified by the loss of history in the city,” he says.

“It’s rare that something actually gets saved; often something that’s really quite worthy ends up getting [destroyed]. So to see something that’s so thrashed, that’s clearly bound for the wrecking ball actually get saved, I think captures people’s imagination.”

Stormont agrees. But she’s not so sure she would go through such an extensive renovation again.

“Ignorance is bliss,” she laughs.

“I knew it was going to be a lot of work, because I had seen Graham on his other projects, but I had no idea that it was going to be two-and-a-half years later and we still don’t have a kitchen.”

© The Vancouver Sun 2007