Buying boom means a ‘problem’ property can easily be fixed and resold

William Boei

Sun

PETER BATTISTONI/VANCOUVER SUN Leaky condos, such as the one (left centre) visible under green and white tarps downtown, are not necessarily money-losers for owners who have the necessary repairs made before putting the unit up for sale, but researcher Nancy Bain says there can be abuses in which leak problems are not fixed and an owner fails to disclose a property’s troubled past to an unwary buyer.

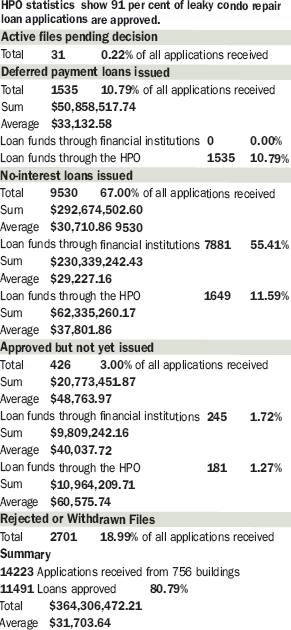

Source: Homeowner Protection Office VANCOUVER SUN

If B.C.’s leaky condo disaster has a silver lining, it’s the province’s hot housing market.

Prices are rising so fast that once a leaky condo is properly repaired, its market value can easily increase by the cost of repairs and more within a few years.

Owners who buy leakers, see them through the repairs and then sell may well come out with a profit.

In fact, says researcher Nancy Bain, that has been suggested as a viable investment strategy: Buy leaky condos cheap in buildings whose strata councils are willing to come to grips with the problem, get the repairs done and sell into a rising market.

The fast-moving housing market is also a reason for cautious shopping: Some leaky condo owners, especially in buildings whose strata corporations can’t agree on a repair strategy, are putting up for-sale signs and bailing out, sometimes without disclosing the problems.

Buyers are often caught by surprise, says Bain, who wrote a research paper on disclosure for Canada Mortgage and Housing. She interviewed 40 condo owners who had unknowingly bought leakers and found that all too often the previous owners knew there were problems but failed to disclose them.

“There are numerous cases where the buyer was not aware of material facts prior to the purchase,” her research paper said.

Bain found property disclosure statements that are supposed to reveal such problems sometimes said there had been no water damage when there had. Strata council minutes were sometimes drafted so as to “not reveal the true condition of the building.” Even home inspectors’ reports were sometimes “couched in soft language” that might raise red flags for knowledgeable people but would not necessarily be noticed by typical homebuyers.

Bain said in an interview she is certain leaky condos are still being sold without disclosure. James Balderson of the Coalition of Leaky Condo Owners agreed.

“Yes, he said, “minutes are sanitized, pages are missing.”

The condo crisis generally occurred for buildings built between the early 1980s to the late ’90s. Since then, condo design and construction has improved dramatically.

Buildings that continue to have issues with leaking have, for the most part, either taken time to show problems or have strata councils that have not taken appropriate action.

Some strata councils make cosmetic repairs and then claim the problem has been fixed, even though engineering studies call for major work. Some buyers have been told a building has been retrofitted with rainscreen technology when no such work has been done, Balderson said.

But it’s a forgiving market, for now.

“As long as the market is hot and fast, when people make ‘a buying error’ they will just resell it,” Bain said. “It will be when the market stops that it all comes to light.”

There doesn’t appear to be any agency keeping track of failure to disclose.

The Better Business Bureau says it refers complaint calls to the provincial government’s Homeowner Protection Office. HPO chief executive Ken Cameron says he doesn’t recall seeing any such complaints. The Real Estate Council of B.C.’s records show only one case in recent years of a real estate agent disciplined for failing to disclose the state of a leaky building.

Bain advises homebuyers to do their homework — ask for all the relevant documents such as strata meeting minutes and engineering reports, study them carefully, ask a lot of questions and do not commit to a purchase until they are answered.

She concedes that research takes time and that in this market, by the time you’ve got your answers the place may well have been sold to someone else. “So you have to weigh off the risk-reward thing.”

One strategy is to do exhaustive research on a building where a condo is for sale and not worry about whether anyone else gets there first. If you find the building has no problems or that it had problems that have been properly dealt with, wait for the next listing in the building. You’ll be able to move fast and safely.

Be very wary of buying in a building where the owners are arguing with each other about how serious the leaks are and what level of repair is needed.

In almost every leaky building, there are owners who refuse to believe the problem is serious enough to warrant spending big money on studies and repairs. When the skeptics are in the majority or when the strata corporation is deadlocked, no repairs are done and the rot only gets worse.

What must be the worst-case scenario is being played out in a building in Vancouver’s West End, where an investor who was renting his unit out found it was leaking and asked the strata council to fix the leak.

That was in 1997. Nine years later, his suite remains uninhabitable and the building envelope has not been repaired, although a number of suites have had individual repairs and some have been sold.

Owners have been suing and counter-suing each other and the strata council, some claiming the council authorizes cosmetic repairs for its friends’ condos and refuses them for dissenters.

Balderson said dissident condo owners in the building are just now getting close to obtaining a court order to force the strata council to undertake building envelope repairs.

The West End building “isn’t an isolated example,” said Bain, a former member of the Real Estate Council of B.C. “So much money goes into acrimony. The community that people have is ruined, and the repair still doesn’t get done.”

The HPO stresses that it’s caveat emptor — buyer beware.

“It is ultimately the consumers’ responsibility to make sure they’re protected, that they take advantage of the protection that’s available to them,” Cameron said.

“No system is perfect, but the system that we have, combined with a diligent consumer who knows their rights, catches as far as we can see most of the problems.”

There is also an element of “seller beware,” said Pierre Gallant, an architect with the Vancouver office of building engineers Morrison Hershfield.

“Many have been successfully sued for misrepresentation,” said Gallant, who has been an expert witness in a number of suits where sellers got caught failing to disclose.

There is some good news: The newer the building, the better the chances are that it has been competently designed and built, and the lower the risk that it will rot.

Cameron says much has been done since the 1990s to improve condo construction.

A robust warranty program backed by major insurance companies has replaced a wobbly building-industry-run warranty scheme that collapsed in the 1990s under the weight of leaky-condo claims.

Home builders and remediators have to be licensed now, as do strata management companies. The provincial government is expected to approve more demanding education requirements soon for residential builders.

Architects, engineers and others have been working since the early 1990s to develop better “building science,” and have produced best-practices guides which, if followed, should prevent most of the problems that led to the leaky condo disaster.

“The housing industry has gone from a crisis to an economic powerhouse,” Cameron said. “Consumer confidence has rebounded, and 135,000 homes have been built with the new home warranty insurance system by licensed residential builders.”

Peter Simpson, chief executive officer of the Greater Vancouver Home Builders’ Association, says the number of new warrantied homes is up to 143,000 now.

The HPO operates a no-interest loan program that has so far doled out nearly $550 million to cover repairs on more than 14,000 leaky condo and co-op units. The province has also forgiven provincial sales taxes of more than $16 million on leaky condo repairs.

Cameron said: “I think it’s quite remarkable how much of a corner we’ve turned in helping those who were stuck with a problem not of their own making, but also the preventative measures of a licensing system and warranty insurance for new construction.”

Most of the new warranties cover labour and materials for two years, the building envelope for five years and major structural defects for 10 years.

There is an option to cover the building envelope for 10 years, but few insurance companies offer it. That worries consumer advocates who point out that in the 1980s and ’90s, leak and rot problems often didn’t surface in the first five years, especially on highrises.

Tom Reeves, a former HPO official who is now director of home warranty operations for Lombard General Insurance Co. of Canada, responds that leaky buildings may not experience “major failure” within five years, but any leaks should be apparent within that time, as long as strata councils and their management companies do proper maintenance and inspections.

Reeves said Lombard, which is new in the home warranty business in B.C., “obviously feels that construction quality in British Columbia is excellent, or we wouldn’t be writing this product.”

His company takes painstaking steps to make sure projects it insures are well-built, he added.

“On a larger project, we’ll review the team, anything from the building envelope consultant to mechanical systems to the architect and the engineers, all those things.”

The technical skills on the project are scrutinized, including the qualifications of the construction trades. “We’ll review plans, details and materials, We’ll review the business plan. All of that occurs at the beginning of the project. During construction, it includes inspections and reviews of inspection reports.”

Asked if consumers can be confident in new B.C. homes, Reeves said they now come with “the strongest defect warranty in Canada for new homes.”

Simpson said HPO surveys show 91 per cent of new home buyers now are satisfied with the quality of what they’re buying.

In Greater Vancouver, where single family homes are rapidly becoming unaffordable for many buyers, more than three-quarters of new homes are in multi-unit developments. Simpson said consumers are not hesitating to buy into them.

“They’re selling out well before they’re even built,” he said. “They’re getting built as they should be built, and they’re being designed more with our West Coast climate in mind.”

Gallant adds: “We build buildings differently than we used to in the ’80s. We have building envelope specialists, we now typically use rain screen, we go beyond the minimum standards of the code in most applications, save the exception of family homes.”

The HPO is trying to get a grip on the single-family-home-building business, which includes many small operators who escape regulation by claiming to be builder-owners, but actually sell everything they build.

“There’s better checks and balances throughout the industry to avoid the mishap of the ’80s,” Gallant said.

“We still see it with some of our projects, immense pressure to hurry and cut corners. That’s human nature; that’s not going to change,” he said, adding that even though the rush to get product to market was a hallmark of the earlier building boom, he does not expect the same problems to occur.

“It’s not built the same, it’s not designed the same and it’s reviewed more often by more people during construction.”

Nevertheless, there will be individual failures and the industry can’t let its guard down, Gallant said.

“In a boom economy is when building failure rates increase, so we must be vigilant.”

Home-buyer advocate Carmen Maretic remains skeptical, saying the building industry is known to have skills shortages and “if you build it wrong, it will fail.”

She is also concerned that when a home warranty provider declines a claim, home owners have no recourse short of hiring a lawyer and starting a legal battle with an organization whose resources are far greater than theirs.

An independent adjudication system like that used by the Insurance Corp. of B.C. might plug that gap, Maretic said.

Louise Murray, who runs the bccondos.ca advocacy website, said the provincial government should be much more active in policing the Strata Property Act.

“Given the spectacular and ongoing failure of multi-unit housing here, how can this province even consider the rampant condo development now everywhere you look, without providing any recourse for conflicted owners?” she asked.

She said a condo equivalent of the province’s Residential Tenancy Office, which provides landlords and tenants with information and offers dispute resolution services, is urgently needed.

Balderson agreed the home-building industry’s performance has improved, but said that happened in large part because so many building professionals, developers and contractors were sued by thousands of unhappy condo owners.

“All that litigation served as a spur to improving the industry,” he said.

© The Vancouver Sun 2006