Hundreds of thousands of British Columbia homeowners have been affected over the years

William Boei

Sun

PETER BATTISTONI/VANCOUVER SUN Tens of thousands of condo units built during the B.C. building boom of the mid-1980s to the late 1990s suffered water damage as wind-driven rain entered the walls of buildings.

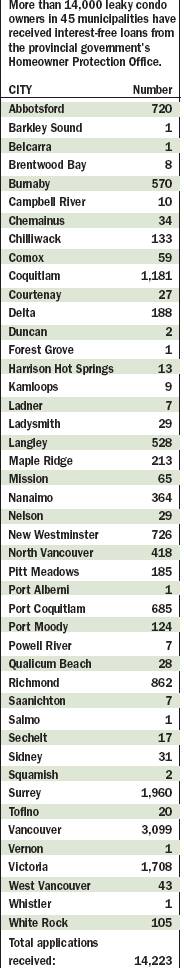

Source: Homeowner Protection Office VANCOUVER SUN Leaky condo loans

B.C.’s leaky condo disaster is entering its third decade. The worst of it is behind us but it is far from over and we are not nearly finished paying for it, or arguing about who is to blame.

The human cost of the disaster is not measurable. Hundreds of thousands of British Columbians have been touched by it.

For some, it was no more than a financial inconvenience. Their homes leaked, and they paid to repair to them.

Others, especially in the 1990s, lost their homes, their savings and their health.

Tens of thousands of condo units built during the B.C. building boom of the mid-1980s to the late 1990s suffered water damage as wind-driven rain entered the walls of badly designed, badly built buildings.

The home building industry’s warranty program collapsed under the weight of the claims, and many homeowners got little or nothing back. They included older couples who intended to spend their golden years in a low-maintenance condo and young families buying their first homes.

In the worst cases, the walls leaked so badly homes were all but flooded. Wet carpets sprouted mushrooms. Moulds, some of them toxic, stained the walls, making some people sick. And the walls rotted.

Some condo owners walked away from their mortgages and their homes. Some slipped into bankruptcy. Some developed respiratory and stress-related illnesses.

There was no government help until the end of the 1990s following two public inquiries, when the province set up its Homeowner Protection Office and offered condo owners interest-free repair loans.

The financial cost of leaky condos is measurable, but only parts of it are being measured.

We do know that the average cost of repairing water-damaged condos has nearly doubled since the Homeowner Protection Office was created. Some figures indicate it has more than tripled.

Government and industry sources agree the cost is going up because:

More and more concrete highrise condo owners are discovering leaks, and they’re more expensive to fix than low-rises;

Low-rise buildings whose owners have put off repairs — sometimes for years — or tried to cover up the problem with cosmetic fixes are coming up for repairs with more advanced rot than buildings that were dealt with early;

Construction costs are rising fast as B.C. rides another major building boom.

One indicator of per-unit repair costs is the interest-free repair loans provided by the HPO.

“The average value of the loans has been going up quite significantly,” said HPO chief executive Ken Cameron, “so it’s now in the $60,000-to-$75,000 per unit range, whereas it used to be in the $35,000-to-$40,000 range.”

The number of low-rise buildings turning up with building envelope problems is past its peak, but a second wave of leaky condos — concrete highrise buildings — is well under way.

“It’s not over,” said Carmen Maretic, a real estate agent who has been advocating for leaky condo owners for years. “It’s very much still a problem.

“People are still dealing with the whole process of evaluating their buildings and going through whether a majority of owners can agree to do repairs.”

Maretic, who heads the CASH (Consumer Advocacy and Support for Homeowners) Society, said HPO statistics show that in the last eight months, the HPO approved nearly $139,000 per day in repair loans.

“As shocking as these costs are, this only represents a portion of the true repair costs as many homeowners do not qualify for HPO no-interest or deferred loans,” Maretic said.

Her figures indicate the average loan has more than tripled, from $19,733 as of March 2000 to nearly $60,500 in the last eight months.

Maretic called on the provincial government to provide more help for leaky condo owners and press the federal government to kick in more money.

Ottawa kicked in about $28 million early on for the HPO interest-free loans fund, but serious negotiations for a larger federal contribution petered out years ago.

One highrise after another, along the New Westminster waterfront, on the North Shore, in downtown Vancouver and elsewhere in Greater Vancouver, is getting its walls stripped down to concrete, scaffolding erected to roof level and green shrouds draped over the building to keep the rain out during repairs.

Advocates like Maretic and James Balderson of the Coalition of Leaky Condo Owners are keenly aware of them, engineers like Pierre Gallant of Morrison Hershfield who oversee the repairs say they’re seeing more leaky highrises relative to low-rises, and the HPO’s Cameron acknowledges there are proportionally more highrises joining the lists of leaky buildings.

On virtually all of them, the outer cladding — usually “face seal” systems attached to the concrete walls with steel studs — has failed to keep the rain out. The fix is to strip off the cladding and replace it with rain-screen wall systems that include a cavity between inner and outer wall components to let any water that gets in drain out again.

Leaky highrises were predicted in the late 1990s by Dave Ricketts of RDH Building Engineering, among others.

“It would be surprising if these buildings did not leak,” Ricketts wrote in the engineering journal Innovation in 1999. “The key difference is the time it takes for the problems to manifest themselves and create a health and safety hazard.”

Gallant agreed. It takes longer for highrises to show problems because, simply, “wood rots faster than steel rusts,” he said.

A face-seal wall “relies on perfection” to keep the rain out, “and therefore fails.”

Low-rises with face-seal walls often leaked in spots where doors, windows, balconies and other features are attached to the walls, and the joints are imperfectly sealed, especially on the upper floors, which are more exposed to rain and wind.

“The exposure on highrises is much higher because the wind exposure is far greater. But the materials are more robust and take longer to decay, typically,” Gallant said.

A few highrises have failed catastrophically: Sections of cladding have let go and plunged to the ground. But most of them just show the same symptoms as leaky highrises — water inside the windows, wet spots and mould on the walls.

Highrise or lowrise, the expert advice is that the longer you put off repairing a leaky building, the more expensive it will be.

Yet there are still dozens if not hundreds of low-rise wood-frame buildings where the owners haven’t realized their walls are rotting, or are refusing to acknowledge the problem, or have tried cosmetic fixes when major repairs are needed, or are deadlocked with their neighbours over whether and how much to spend on repairs.

Many strata councils are pursuing slow-moving lawsuits, trying to recover at least some of their repair costs from developers, contractors, architects, engineers, window manufacturers, municipal governments — anyone connected with their leaky buildings with deep enough pockets to sue.

Most of the suits are settled through mediation and with non-disclosure agreements attached, so there is no public record of the average settlement. But lawyers say strata councils typically get 40 to 60 cents back for every dollar they spend on repairs.

For those who can’t reach a consensus, or can’t muster the resources to get through the daunting process of hiring technical and legal expertise to assess the damage, finance the repairs and recover at least some of the cost, it’s an unending nightmare.

“The longer you wait, the more the damage,” said Gallant. “And the cost is going to be higher not only because there’s more damage, but because construction costs are going up. So putting your head in the sand is not going to solve the problem.”

“Many people are still suffering,” Maretic added, “particularly those that went into bankruptcy and those that have health consequences.”

After all these years, no one can yet say with any certainty just how big the problem is.

There are no solid statistics for the number of leaky condos or how much it is costing to fix them, although the HPO is sticking with a five-year-old estimate that about 65,000 condo and co-op units have suffered water damage and the total repair bill will be about $1.5 billion.

But there is no registry of leaky condos, no comprehensive list, no certainty about how many buildings have been touched by the rot.

“No one knows the extent of B.C.’s leaky condo crisis,” said Louise Murray, who operates the bccondos.ca advocacy website, “because, unbelievably at this late stage in the game, no one is tracking it.”

It is guesswork whether the HPO’s loan statistics reflect actual repair costs.

Only those who can show they don’t have the assets and income to shoulder the cost of repairs, and are prepared to follow the HPO’s repair guidelines, are eligible for the loans. Those with more resources, whose homes may be more expensive and cost more to fix, are not eligible and not counted. Those who try to make do with patch-work repairs are not counted. Not surprisingly, many suspect the HPO’s numbers are low.

“We’ve never trusted their estimation,” said Balderson. “We continue to think they underestimate the magnitude of the problem and the total cost.”

Balderson says only 20 per cent of condo owners qualify for HPO assistance — leaky condo welfare, he scathingly calls it.

That means 80 per cent of the problem is not accounted for by HPO statistics, and Balderson notes the 80 per cent includes upscale buildings where no one qualifies for loans, and repairs run as high as $125,000 per unit or more.

“I think their number’s low on total costs incurred,” concurred John Singleton, a lawyer whose firm, Singleton Urquhart, has defended many building professionals in leaky condo suits. “My sense is it’s over $2 billion.”

That’s for residential buildings. The HPO counts only leaky condos and co-ops. But they were not the only buildings affected by design and construction problems in the ’80s and ’90s.

“We have seen failures in all kinds of buildings,” said Gallant, whose company is one of the region’s leading engineering firms for building remediation work.

Rental housing, social housing, office buildings, schools, churches, even shopping malls are infested with the same problems as leaky condos. Water gets in the walls, it can’t get out again, and the wall components slowly rot. We don’t hear much about them because they don’t have angry owners clamouring for media attention. Gallant says their owners file insurance claims, do the repairs and file lawsuits with no public fanfare.

So what’s the grand total? Nobody knows.

Might it be higher than the official estimate?

“It might,” Cameron conceded. “It’s hard to say.”

Gallant and others with an overview of the construction industry guess that residential housing probably accounts for the majority of the damage. So if the real cost of repairing leaky condos is more than $2 billion and repairs to all other types of buildings amount to only one-third of the total, the bills add up to at least $3 billion — double the province’s estimate.

© The Vancouver Sun 2006