Graduate students envision communities becoming more complete as the green zone is protected and alternatives to the car are presented

William Boei

Sun

Concept of livable neighbourhoods in Vancouver, such as these work-and-live buildings along Arbutus, is expected to continue to spread. Photograph by : Ian Smith, Vancouver Sun

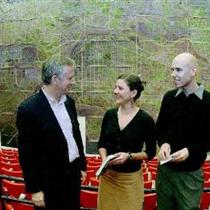

UBC professor Patrick Condon (left) speaks with Masters in Landscape Architecture students Niki Strutynski and Greg Rouleau about trends in population growth and land-use issues. Hanging behind them is a composite map of the Lower Mainland. Photograph by : Stuart Davis, Vancouver Sun

Think of some of Vancouver’s livable neighbourhoods — along Fourth Avenue and Broadway on the west side, on Commercial Drive on the east side, and increasingly along Main Street in the centre.

There are street-level shops, restaurants and offices, condos on upper floors, apartments and single-family homes around the corner. Many residents can find their daily needs within a few blocks’ walk along safe tree-lined sidewalks, and transit service is frequent and fast.

Imagine such communities along King George Highway in Surrey, North Delta’s Scott Road or Lougheed Highway in Coquitlam.

It’s an achievable vision, two University of B.C. landscape architects said Monday as their graduate students showed off their end-of-term projects.

Patrick Condon’s master’s degree candidates in UBC’s landscape architecture program produced a huge map — nine metres by 13.7 metres — showing what Greater Vancouver might look like in 50 years with its population doubled to four million.

“Places like Whalley or Scott Road or Coquitlam Centre can potentially become much more interesting places to be and provide much more of the urban and cultural amenities that people seem to want,” Condon said.

His students made a huge assumption: that growth in Greater Vancouver can be concentrated around “transit nodes” in the town centres that are outlined by the regional district’s Livable Strategic Plan, rather than sprawling willy-nilly into the Fraser Valley.

“Our communities become more complete, the green zone is protected, there are alternatives to the car presented,” Condon said.

“It’s a big assumption that those things are going be adhered to. We certainly hope that they are. If they are, the map shows what the communities would look like — much like they do now, but in many respects better, in the same way that most people think downtown Vancouver has become much better as its population has doubled from 40,000 to 80,000 in the last 10 or 12 years.”

The students’ map shows more than 100,000 new buildings in the region, many of them in the designated growth areas along major transit routes, based on the regional growth strategy, municipalities’ official community plans and population growth projections.

“We asked them to do it in a way that met a number of sustainability principles such as providing as many jobs close to houses as possible, making sure that you have a mix of housing types, protect and/or restore environmental systems and make sure that everybody lives within an easy five-minute walk of transit services,” Condon said.

Lawrence Frank’s class in land use and transportation in UBC’s school of community and regional planning, meanwhile, focused on how the provincial government’s Gateway Project will affect the region’s growth.

The Gateway plan calls for new truck routes on the south and north shores of the Fraser River, expanding the Trans-Canada Highway between Langley and Vancouver and twinning the Port Mann Bridge.

But the students warned that only building more road capacity could bring about a “triple convergence” as travellers who used to take other routes, or travelled at off-peak hours or used other means of transport all converge on the expanded highway at the same time.

They noted that the Gateway plan is part of a strategy to turn Vancouver into a major container port hub to distribute goods from overseas throughout North America, but that it would channel all the resulting traffic through the Greater Vancouver metropolitan area.

One alternative, they said, could be to expand rail capacity to move the goods through Vancouver, perhaps as far as Alberta, to an inland terminal from where they would be distributed throughout the continent.

They also said container truck traffic could be distributed around the clock, which would require the container ports to expand their hours from the present 7 a.m. to 4 p.m., which forces trucks to compete with daytime commuters for road space.

And they suggested tentative plans to make the twinned Port Mann Bridge a toll bridge run by a private operator could result in pressure to maximize the amount of traffic using the bridge, since the more traffic that crossed it, the more money the operator would take in.

Frank said that kind of scenario can be averted with creative planning, such as applying tolls only during peak traffic hours to encourage traffic to use it at other times.

“I think it can be done,” he said, “but it may need a new model for investment, perhaps a new hybrid between public and private investment.”

Condon said there are hopeful signs for denser development, especially in Surrey, despite its approval of several controversial “big-box commercial developments and far-flung business parks.”

A recent study of the Vancouver, Seattle and Portland regions by Seattle’s Northwest Environmental Watch found that only Greater Vancouver has suburban areas, notably Surrey, that are becoming “substantially more efficient” in their land use and increasing average densities.

“So the underlying trend line is favourable,” Condon said.

The development industry is prepared to play ball with regional planners, said Urban Development Institute executive director Maureen Enser, as long as local governments pave the way with viable policies.

“One of the challenges that we face as an industry is to be able to increase densities around transit nodes without being penalized for doing so,” Enser said.

That may mean reducing the high development fees builders now face if they want to develop in high-density areas.

“You have to make those units as affordable as possible,” Enser said. “Therefore you need to keep those costs associated with development as reasonable as possible, so the end product is fairly priced and it does become an attractive place to live.

“If it’s sensible, it’s well planned and it’s easy to build the product that’s needed and there is a demonstrated need, those are all ingredients for success.”

Frank said the coming months are crucial as provincial Transportation Minister Kevin Falcon prepares to reveal the details of the Gateway Project and a new regional district board settles on a development strategy for the next decade.

Frank said the region would be foolish to reject huge inflows of cash from senior governments and investment from private partners to build transportation infrastructure.

But expanding road capacity without coupling it to the regional strategy will send low-density development sprawling into the Fraser Valley, he said, and the region needs to establish benchmarks so it can measure how proposed projects will affect its future.

“We have to find ways to use those funds in ways that don’t undermine our ability to have the quality of life that we’ve worked so hard to create.”

© The Vancouver Sun 2005