‘Birthplace of Vancouver’ is being reborn again into a Soho-like community

Sun

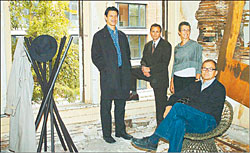

When are four adults in a room news? When the room is in a 115-year-old building in Vancouver and the four adults represent three separate development initiatives in Gastown and two generations of refurbishment and rehabiliation there, that’s when. A participant in the first Gastown rejuvenation in the 1960s and ’70s, Niels Bendtsen took a seat for this group portrait, the chair following him from Inform Interiors across the street from the Grand Hotel. Behind him is his wife, Nancy, and partner at Inform; Jan Stovell; and Grand Hotel owner Robert Fung. The coat rack, too, crossed the street from Inform. Water Street neighbours, the Grand and Terminus hotels are monuments to Vancouver’s ascendency to first-city status in the Lower Mainland. About the Grand, a report from city hall staff to council notes: ‘The building’s original name, the Granville Hotel, celebrated its location in the Old Granville Townsite. When the hotel was expanded with a rear addition in 1903/04, its name was changed to the Grand Hotel, an indication of how the settlement of Granville had been absorbed into . . . Vancouver.’ The next-door Terminus, staff commented, ‘is valued as an early Gastown hotel, representative of the area’s seasonal population in the late 19th and early 20th centuries

Gastown is undergoing another birthing experience, ”risk oblivious” new-home buyers, daring property developers and Vancouver city hall among the midwives.

Gastown, as city hall documents say, is the “birthplace of Vancouver.” The colonial government in Victoria conducted the first land sale there in 1870. The first conversion of the Victorian and Edwardian buildings there occurred a century later.

The current revitalization, accordingly, is the third birthing moment there in about 135 years. The renovation about five years ago of the Old Spaghetti Factory building, itself a refurbishment in the first rebirth, heralded the current round.

But the pursuit of a “Soho-like” neighbourhood hasn’t been easy.

The city’s poorest neighbourhood — the downtown eastside — is next door, a proximity that has scared off potential investors for years.

Gastown is a confined space. The passage of a cement truck, for example, is more time consuming and more costly here than elsewhere. Many of the old buildings have suffered substantial deterioration after years of neglect.

Still long-time property owners such as Reliance Holdings Ltd. and Nancy and Niels Bendtsen of Inform Interiors and newer investors like the Salient Group are commited to making the effort.

City hall is also committed to helping them make the effort, with a heritage-preservation which includes property-tax relief.

The incentives are also being offered to Chinatown and Hastings Street, with the hope that all three communities will reap economic benefits.

“I have faith all three areas will improve,” councillor Jim Green says.

The mayoral candidate attributes the renewed interest in the three areas to the Woodward’s revitalization and a new bylaw.

As anybody who has read a newspaper or watched the news recently know, he is the city’s leading champion of the latest Woodward’s plan, 700 new homes in a 40-storey tower, 500 of them market housing, 200 of them social housing.

“Woodwards is seen as the rebirth of that area of the city, and the animosity that used to exist between Gastown, Chinatown and Hastings in rapidly declining,” says Green.

He adds another reason for the improved relationship is downtown eastside residents no longer fear being displaced, as so many were before Expo 86.

The main reason for that, says Green, is a bylaw he first proposed to protect SROs (single-resident-occupancy rooms) in 1984 was finally passed 20 years later.

“People in the area can now welcome new development without fear of being displaced,” he says.

Green adds Gastown specifically has enjoyed a resurgence in tourism thanks to Storyeum — an interactive museum about B.C’s history. It was created in a former parkade.

“Gastown is fabulous. It’s like the sleeper area of town,” Nancy Bendtsen of Inform Interiors says.

“Gastown is going to become like Yorkville in the ’60s or Soho in New York. The cool area of town.”

Niels Bendtsen bought a historic building, at 134 Abbott, 40 years ago and renovated it to showcase his store and provide office space upstairs. The couple also owns a building across the street, at 50 Water Street, and plan to expand their furniture showroom.

Another heritage building to be among the first to undergo extensive renovations was the landmark Old Spaghetti Factory, at 55 Water Street, in 2000, by Reliance Holdings Ltd.

The company also built the modern glass atrium adjacent to the Old Spaghetti Factory, a former parking lot, that rents to the high-end clothing store Richard Kidd.

Reliance also has a new 10-storey building with 58 rental suites and two large retail spaces at 33 Water and another building with 130 units which could either be rental or live/work.

“Gastown is a good market for rental because a lot of young people are attracted to the area,” Reliance representative Jan Stovell says. “We call them the ‘risk oblivious.’ They don’t want to be in an area that is sanitized. It’s the new edge neighbourhood the way Yaletown was 10 years ago and Kitsilano 25 years.”

Stovell adds when Reliance began marketing the rental units at 55 Water Street “no one came in and said ‘is this neighbourhood safe? Where can you buy groceries? Why are people panhandling or will I get ripped off?’ They don’t ask those kinds of question.

“People who come down here already know about the downtown eastside (nearby). They know what they are getting into,” says Stovell.

He adds the area is attractive to many creative business operators like gallery owners and funky restaurants and shops.

The residents, he says, are in their 20s and 30s, and work in occupations like software technology, graphic designs, film and architecture.

And while years ago there was a push by merchants in Gastown to rid the area of panhandlers, says Stovell, that fight appears to have ended.

“We used to have an ultra polarized turf war but people have buried the hatchet and both groups go about their business,” he says. “Now we have the well-off, who are not that ostentatious, with busy active careers who like living in the core, going out for dinner, immersing themselves in urban living, living in the heart of the inner city mixed in with the grit.

“In Gastown there’s such a spectrum of society. You can see what people have achieved through effort – from the guy in the Bentley to the guy with his hand out asking for money.”

While, Gastown has historically been an area for tourists to shop for B.C. souvenirs many of the retailers today are aiming to attract an upper end local market as well.

“There’s been a concentrated effort among a core group of property owners to improve the buildings and to target a certain kind of retail,” says Stovell.

Wanting to tap into the upper-end market are newer developers like Salient’s Robert Fung, who at only 39 years of age is hoping to do on a smaller scale what Concord Pacific did years earlier for Yaletown.

Indeed, Fung, whose first project was in 2003 with the renovation of the Taylor Building in Gastown, worked for Concord for eight years.

The Taylor building, opposite the famed gas clock, was converted into 22 suites and quickly sold out for an average of $320 a square foot at the town – rates that typically were seen in more desirable downtown locations.

“Gastown in the past was the area where people would come in and find cheap buildings and do cheap jobs on them,” says Fung. “We felt these buildings are fantastic projnects in the context of improving the entire city.”

Still, Fung says many of the larger developers in the city think he’s crazy to be developing in an area they still view as high-risk.

“A lot of the large developers think I’m out of my mind. These buildings are extremely intensive, hard to work with in the existing forms so people have snubbed their noses at them. But that’s why I like it. I’m up to a good challenge.”

Still, Fung and his wife prefer to live in Kerrisdale themselves because they are the parents of three young children, ages three, two and a newborn.

“One of the problems (in Gastown) is the cost is so high it’s difficult to build good quality family housing in the core,” says Fung.

His target market group for his “boutique-size projects” are buyers who themselves are very unique and want a unique home.

“It’s very individual. It has less to do with gender or age and more to do with mind-set. The marketers thought it would be the young urban male (moving to Gastown) but we have a lot of single women, some same-sex couples, guys, artists – it’s across the board. All have a strong sense of individuality.”

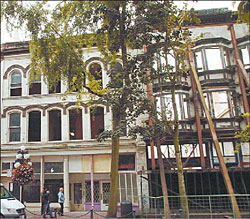

Fung’s current residential project is the conversion of the side-by-side Grand and Terminus hotels. The goal is 46 new homes. Prices are not yet set.

“With the Terminus Building we’ve really tried to do a building with a great sense of style, highly identifiable and in some ways iconic for the area. A building that is a pleasure to live in,” says Fung of the project, at 36 Water Street.

The Terminus Buildings will also have a small retail componet, of about 5,000 square feet.

Another Salient project is the renovation of Gaolers Mews, where 40 per cent will be utilized as live/work spaces and the remaining 60 per cent will be retail/office space.

This landmark building once housed the city’s oldest parking garage and a courthouse and jail. The stones for the Alhambra Building, where the Salient offices ar located, in the mews was laid in 1886.

“The history of our city is important and the inventory of real heritage buildings is important. Salient is interested in this district and to effect a major change in the city,” says Fung.The guy who has to organize crews and equipment to actually preserve the facades of the city’s older buildings during construction behind them, contractor Roland Habler, thinks it makes more sense to demolish at least some of the structures he’s preserving and build new. ‘Sometimes we wonder about the sanity of doing the kinds of things they want with these heritage buildings. . . . .’We’re trying to hold up and retain facades over 100 years ago. Some of it is a total joke.’Preservation, because it is time-consuming, costs anywhere from 20 to 35 per cent more than building new, he says.’We all agree having the heritage component is wonderful but why don’t they do like in many European cities where they get craftsmen to mimic exactly what was done before?’