The impact of the architecture of Fred Hollingsworth is equally important to that of Arthur Erickson, says curator-author

Kim Pemberton

Sun

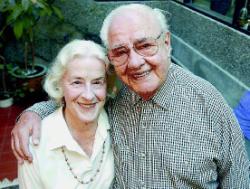

CREDIT: Ian Smith, Vancouver Sun Fred and Phyllis Hollingsworth continue to live in the first home he designed in 1946. It is where they also raised their children.

CREDIT: Ian Smith, Vancouver Sun The Hollingsworth trademark is a house that respects its site and a strong emphasis on ‘bringing the outside in.’

The “West Coast style” of bringing the outdoors in and using natural materials as much as possible in a home is well-known to British Columbians but have you ever wondered who helped create this internationally-acclaimed and popular form of architecture?

The name Fred Hollingsworth may not be as well-known to the general public as Arthur Erickson or Ron Thom but this quiet, unassuming 89-year-old North Vancouver resident can claim the distinction of helping create a design aesthetic that has become a hallmark of coastal living.

“I’m a very big fan of Fred Hollingsworth. He’s really significant in terms of setting a style and standard,” says Greg Bellerby, curator of Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design’s Charles H. Scott Gallery and co-author of Living Spaces: The Architecture of Fred Hollingsworth.

This long overdue book, devoted entirely to Hollingsworth’s six-decade career, is expected to be in bookstores in October.

“He and Ron Thom and colleague Ned Pratt really promoted modernism in the late ’40s and early ’50s. There was only a handful of guys that really established this ‘West Coast’ regional style. While Arthur Erickson is certainly the person who comes to mind when you talk about Canadian architecture there are others like Fred who have had an equally important impact.”

Bellerby says Hollingsworth designed more than 60 houses, most of them located on the North Shore in the Capilano Highlands.

“That’s a lot of homes for one architect to design. Fred was really interested in providing houses that people could afford. Many were built for $10,000 and today would be worth over $1 million,” says Bellerby.

Hollingsworth, and his wife of 56 years, Phyllis, continue to live in the first home he designed in 1946 and where the couple raised two daughters and a son.

The stripped-down, modular home smudges the lines between indoors and outdoors to achieve the architect’s goal of blending in with its forest setting. The house exemplifies the unpretentious style associated with American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, who Hollingsworth trained under as a young man.

In an interview with The Vancouver Sun, Hollingsworth’s bright mind and humility are evident. There’s not a trace of self-importance when Hollingsworth describes his own remarkable early years in architecture.

“I was very interested in Frank Lloyd Wright so I went down there and visited,” he says.

“I found him extremely interesting. He was a little guy that would shoot you a look with these steel grey eyes and you better have the answer. They’re still talking about him. He’s invented so much in buildings others still haven’t the guts to do.”

Hollingsworth notes Wright continued to design until his death at age 92.

Hollingsworth himself continues to remain active in his retirement, and until recently was a member of the North Vancouver District Design Panel. (He once served as a district councillor and was instrumental in setting up its planning board.)

He also served as president of the Architectural Institute of B.C. and the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, and has mentored many younger architects over the years. Among them is his son Russell Hollingsworth, who has been designing homes since 1973.

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

“He’s a real Renaissance man, a tremendous musician, painter, sculptor, designer of airplanes. There wasn’t much he didn’t do,” says Russell. “He had quite an influence in the local field, but he was the kind of practitioner who never sought the limelight. He just drew.”

Remarkably, all of Hollingsworth’s designs are by hand. He still doesn’t own a computer, now a standard tool of architects.

And while Hollingsworth senior has won his share of design awards over the years, including two Massey Awards, Canadian architecture’s most prestigious award, the upcoming book is the first devoted solely to his work.

“I’m really excited for him to get recognition for his contribution,” says Russell.

As for Hollingsworth, he is quick to name other local architects whose work he admires — among them Paul Merrick and Barry Downs. But he’s disappointed others in the profession are not taking more risks in architecture, with many accepting the classic “heritage-style” residential building that is so popular today.

“Buildings are actually going backwards and that’s scary to me,” says Hollingsworth. “Architecture is supposed to be progressive. But at the present moment residential architecture is in decline. They are not building what they want to live in. They build what will sell.”

Hollingsworth adds that it isn’t entirely the fault of architects because clients today seem less willing to try innovative ideas. “Most people don’t want to be bothered with that. They’re not really looking for what they haven’t seen before.”

Hollingsworth considers himself fortunate that he was given the opportunity to try new ideas during his career. It’s ironic though, he adds, considering the limited budgets available to architects in the early days.

“People now are coming in with zillions of dollars,” he says. “They’re all on this big size kick — everything they pour into the home is big. Even the equipment is big, like these big-screen TVs. It’s ridiculous. You don’t need a TV the size of a wall.”

For Hollingsworth the ideal house is a simple one, without heat loss, and where its owners can enjoy life and “literally live in the backyard.”

“I’ve often said if you could build a house without a roof and keep the rain out it’s the ultimate — to give the feeling of bringing the outside in,” he says.

Bellerby adds other trademarks of a Hollingsworth home are that it respects its site and uses indigenous materials, like Douglas fir, staying “true to those materials.”

“He would never paint the wood — he’d stain it. He would never use artificial laminates, and he would be sensitive to environmental conditions — using passive solar to heat and cool the rooms and being sensitive to open plans,” says Bellerby.

One home that showcases the best of Hollingsworth is at 4710 Wood Valley Place. It has recently gone on the market at slightly under $1 million. The 1,800-square-foot, one-level house was built in 1973 for Norm Rudden at a cost of $57,000.

“We took a long time to design that — to get them [the client] to build a circular living room,” recalls Hollingsworth.

“I wanted to start doing something with geometric tools. You get a design going where it becomes abstract art, when you look at it to see what kind of space relief you get moving from glass to solid walls.”

The house feels like a sanctuary with a sense of being in nature even when you are indoors. Curves are evident throughout, from the front door, to the circular living room to circular skylights in the kitchen, hallway and master bedroom. The entire south-facing wall is made of sheets of glass, again blurring the line between indoors and outdoors.

“Architecture is a big part of life. I like doing houses but they are the hardest to design — you have to think about its functions. A place to cook, to entertain, to relax. We spend so much time in these little buildings we call home. Surely this is the place to spend money to feel good,” he says.

© The Vancouver Sun 2005